If you have immigrant ancestors who arrived in the U.S in the 1900s, these 7 sources can help you track their journey—perhaps even to that overseas hometown, so crucial to your genealogy success!

(Thanks to Legacy Tree Genealogists for providing us with this guest blog post. Learn more about them below.)

Do you have an ancestor who came to the United States in the 20th century? If so, you’re in luck, as there are a variety of resources available to help you learn about their journey to the United States and where they came from. The biggest challenge in tracing the ancestry of immigrants is that you must first identify their exact hometown (not just country or region) before you can locate records in their home country. Luckily, there were a variety of records created when an immigrant came to the United States in the 20th century that can provide helpful clues for finding their exact place of birth.

7 record types for finding 20th-century immigrant ancestors

Naturalization and alien registration records

Naturalization records were created as part of an application for citizenship, while alien registration records were created for any non-citizens living in the United States. Both sets of records can contain a wealth of information about immigrants, including their hometown, family members, identifying information such as birthdates or physical descriptions, and when and how they traveled to the United States.

After 1906, there were three parts to naturalization records: a declaration of intention (sometimes called 1st papers), a petition for naturalization (2nd papers) and the naturalization certificate given if citizenship was granted. The declaration of intention is the most useful for genealogical purposes, as immigrants were required to state their birth dates, often family members’/spouses’ birth dates, and usually their hometowns.

Naturalization records were kept by the various federal, state, and county courts, and many have been digitized on various genealogy websites. Naturalization records can be found at the National Archives, FamilySearch.org, and Ancestry.com. After the Alien Registration Act of 1940, all immigrants to the United States were required to register and be fingerprinted. Alien Files began to be kept in 1944 and are now held by the National Archives.

(Editor’s note: Genealogy Gems Premium e-Learning members can also learn about World War I-era enemy alien affidavits, required for all non-naturalized U.S. residents, in the Genealogy Gems Premium Podcast episode #146.)

You can narrow down the time period your immigrant ancestor naturalized by checking various censuses which asked citizenship information (1900, 1910, 1920 and 1930). The 1920 census is particularly helpful as it asked the year of naturalization in addition to the year of arrival. There were three codes recorded in these columns: PA (has submitted papers), NA (naturalized) or AL (alien—never applied to become a citizen). Knowing where they were living at the time of naturalization will help you narrow down which court they may have used.

Keep in mind that until 1922, married women (and their children) were automatically given the citizenship of the husband (if he was a citizen, so was the wife; if a woman married a non-citizen she lost their citizenship until he became a naturalized citizen). Prior to 1922 wives did not need to apply separately, so there will almost never be naturalization papers for married women—you’ll need to look under their husband’s name.

Passenger lists

Passenger lists were created to document the travels of immigrants and are organized by ship. Some list the travelers’ hometown and their closest living relatives there, which can be extremely useful in linking families. Keep in mind that this will usually be the immigrants’ most recent place of residence (which is not always the birthplace).

When searching passenger lists, be sure to check both emigration and immigration records. Passenger lists created at the point of departure and the port of entry and may give slightly different information. For example, the Hamburg Passenger Lists for Germany recorded those leaving, while the New York Passenger Lists give arrivals—you may find your immigrant on both.

United States passenger lists will often also state the relative they are going to meet who is already in the United States—this can help in differentiating people of the same name. (Another bonus for Premium eLearning members: learn about emigration records in Premium Podcast episode #135.)

The port they came from or arrived in can also give clues as to where they were from in the Old Country—people generally immigrated and settled with others who were from the same place. While many of passenger lists have been digitized on the big genealogy websites such as FindMyPast.com, Ancestry.com, and FamilySearch, do not overlook smaller collections like the Immigrant Ancestors Project, which focuses on other emigration records from smaller ports.

Canada Border Crossings

If you are not finding your immigrant in United States passenger lists, see if they came through Canada. Many immigrants arrived in Canada first and then crossed the border to the United States. Keep in mind that only immigrants who came through ports or trains were recorded—if they crossed by horse or car they will not be included in the records. These records vary but often include the name of the immigrant, who they were going to join, their last residence and family member there, their place of birth, and any previous visits to the United States (4). Both Ancestry.com and the free FamilySearch.org have digitized records border crossings to the U.S. from Canada beginning in 1895 (FamilySearch’s go to 1956 and Ancestry.com’s to 1960).

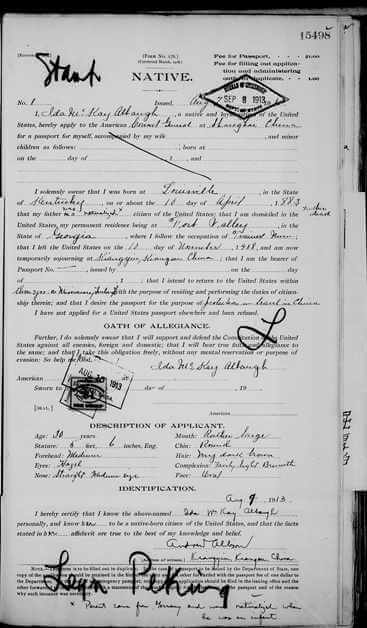

Passport applications

Did your immigrant ancestor ever apply for a passport? Many immigrants went back to visit family in their home country for a few months or even years, before returning back to the United States If they had already become a citizen, they may have applied for a passport to travel. These records can give you a wealth of information about the person who applied but also sometimes their parents.

If you are stuck on an immigrant, look for records about their children—they may provide valuable clues. For example, my great-great aunt applied for a passport in 1918 to be a missionary in China, and she stated that her father had been brought over as an infant from Germany with his parents, who had then naturalized. However, on her passport renewal she stated he was born in Baltimore, so his exact birthplace is still a mystery. However, the passport provided an important clue—now I know to look in the area around Baltimore for naturalization records that could mention his parents. (Click here to read a Genealogy Gem listener’s success story using passport applications and more information on finding them.)

Church records

Many immigrants attended church in their new town along with others from their homeland. Records created at the church, such as baptisms, marriages, and burials, can often provide information about where they came from. Some of these churches even conducted services in the native language of their congregants (i.e. German). These records can be challenging to locate as many of them are still kept by the local churches and have not yet been digitized by the major genealogy websites, but they are well worth it. Try contacting the local church to see if they still have records or know where the records are now. It’s polite to offer a small compensation for their time. Click here to find a list of articles on this website about all different kinds of church records.

Foreign language newspapers

A little-known fact about immigration is that many immigrant communities published local newspapers in the language of their homeland in their new community as a way to stay connected. These newspapers often include birth, marriage and death announcements relevant to the community of immigrants and may list your ancestor. Many of these newspapers are listed on the Library of Congress website Chronicling America, covered in detail in an exclusive interview in the Genealogy Gems Premium Podcast episode #158. (If you’re not a Premium member, consider checking out Lisa Louise Cooke’s book How to Find Your Family History in Newspapers or click here to read articles relating to newspaper research on our blog.

For more help finding immigrant ancestors….

Thanks to Mckenna Cooper, a researcher for Legacy Tree Genealogists, for writing this guest article. Legacy Tree Genealogists is a worldwide genealogy research firm with extensive expertise in breaking through genealogy brick walls. To learn more about Legacy Tree services and its research team, visit www.legacytree.com. Exclusive Offer for Genealogy Gems readers: Receive $100 off a 20-hour research project using code GGP100! (This offer may expire without notice.)

If you prefer the DIY approach to finding your immigrant ancestors rather than hiring assistance, Genealogy Gems is here for you! We gave you lots of links above to further reading. You may have noticed that Genealogy Gems Premium eLearning provides even more resources for you–why not consider whether this may be a good option for you?

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links and Genealogy Gems will be compensated if you make a purchase after clicking on these links (at no additional cost to you). Thank you for supporting Genealogy Gems!