To learn how to research your ancestors who migrated west you have to take a deeper look at the Westward Expansion. Understanding the pulls of the time will help you discover how or why your ancestors went west. Finding a pioneers path of migration isn’t always easy. Legacy Tree Genealogists has a team of specialists very experienced in answering the questions that arise while following your ancestors west and can help you reconstruct the details of their journey westward.

The Pull of the West

Settlers headed west for many reasons, among them were land, gold, religious freedom, military service, and perhaps to escape the law. Whether they traveled by boat, wagon, on horseback, or even on foot, the hardy men, women, and children that braved the dangers of the Old West faced many hardships. War, disease, starvation, and storms plagued western settlers every step of the way. The perilous and transient lifestyle of the pioneers also left a lasting effect on the surviving paper trail. Those records, if found, can allow modern researchers to reconstruct the paths they took on their journey westward. Though it can be quite difficult to recover their stories today, the rewards of doing so can be tremendous, revealing the connections everyday people had with storied events that have grown even more legendary with every passing year.

Land, Land and More Land!

An important thing to keep in mind is that the primary reason most people moved west was the availability of vast tracts of land west of the Mississippi River after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. With that one purchase of land by the federal government, President Thomas Jefferson nearly doubled the size of the United States. In less than twenty years, Missouri entered the United States, in 1821. In subsequent treaties and wars, the United States acquired most of the remainder of the Great Plains, Rocky Mountain West, and the Pacific Coast. The rush to take up the millions of acres of new land and search for riches buried in the earth began in earnest after 1830, with the advent of the Oregon Trail and the seductive allure of the California gold fields in the 1840s. However, in truth westward movement had been an integral part of American life since 1607.

Following Your Ancestors West: Where to Look

Among the most important sets of records for tracing western settlement in the United States are the documents held by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management at the General Land Office. This federal agency houses approximately 9 million land records dating back to the late 1700s. After a gargantuan indexing and scanning campaign, many of these records are now searchable and available to view at the agency’s website, glorecords.blm.gov. Searching for an ancestor in this database produce a number of hits that can help you place your ancestor along various waypoints to the West. Individuals often bought and sold federal land quickly, so many of these purchases might not reflect actual settlement. However, they can give you a good idea of an ancestor’s general path of migration.

In addition to the county deed records often found along an ancestor’s way west, another important set of land records is the mound of documents produced as a result of the Homestead Act. Though images of the land patents issued under the Homestead Act will usually be found at the General Land Office website, another crucial group of associated documents not found there is the Land Case Files. These files contain the original application for homestead land, which often include land descriptions, and sometimes citizenship documents and affidavits of witnesses.

Regardless of where they were created or recorded, land documents provide critical, and sometimes the only, documentation of an ancestor’s westward migration.

Census, Military, and More

While not exactly the same as land records, census returns can also document the migratory path of your ancestors. If the head of household is missing for an ancestor’s family in the 1850 census, try searching his name in the census index for California. You just might find him listed in one of the counties in the gold fields, possibly living in households full of single or married men seeking their fortunes in the far western country. Even if he is listed at home in 1850, check the returns for California. Occasionally men would be counted twice: once at home with their families in the East, and again in a camp in California, on the other side of the continent.

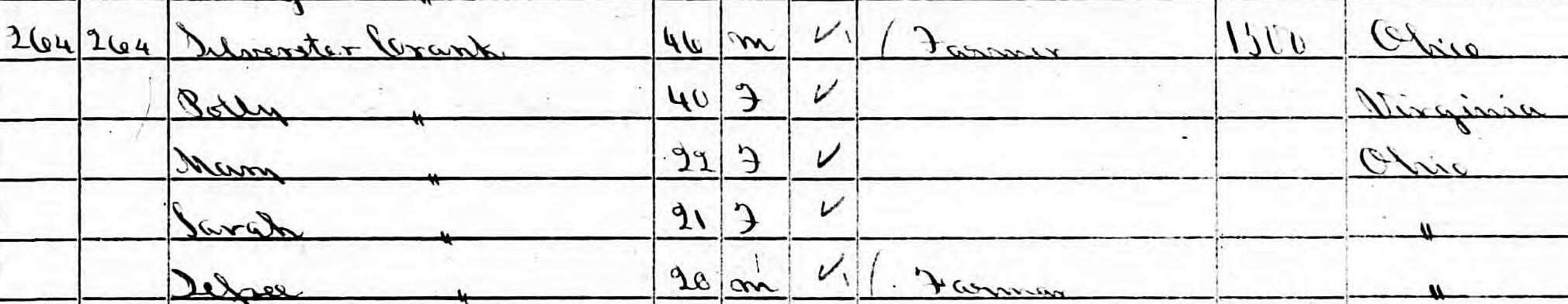

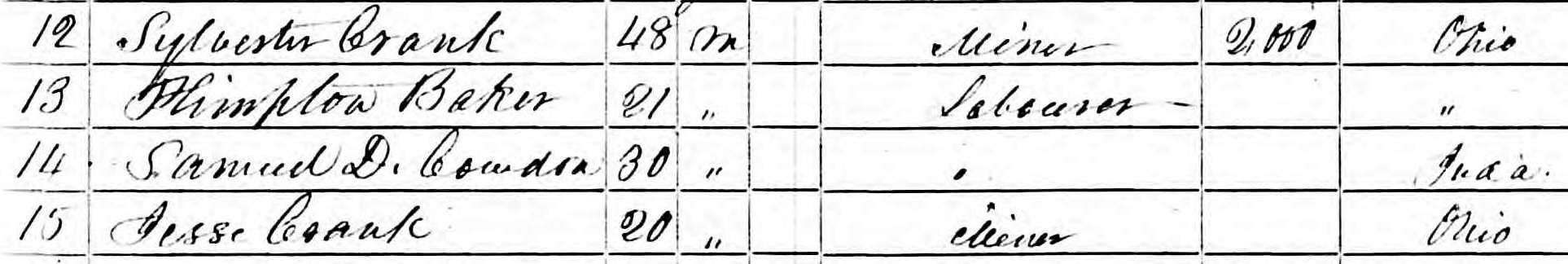

I learned this firsthand when I found an ancestor named Sylvester Crank living with his wife and children in Clinton County, Missouri, in the 1850 U.S. Census. I also found him listed in a household full of only men the same year in Placerville, El Dorado County, California, working as a miner. His son Jesse, also a miner, was listed in both households along with his father, who was close to fifty years old. Placerville was at the epicenter of the then exploding California Gold Rush and had only recently been known as Hangtown, after the predilection of the local judges to resort to the rope.

Sylvester Crank recorded as living with his wife and children in Clinton County, Missouri, in the 1850 U.S. Census

Sylvester Crank and son Jesse Crank also recorded in the Placerville, El Dorado County, California 1850 U.S. census

If your ancestor served in the regular U.S. Army during the period of westward expansion, you’re in luck. U.S. Army enlistment registers have been preserved beginning in 1789, and running to 1914, when the last vestiges of the Old West had mostly been swept away. These enlistment registers often include place of birth and a personal description. They also allow you to trace the path of your Army ancestor in the West because they show each post he was stationed at throughout all of his periods of enlistment. These records make it possible to trace your ancestor from fort to fort throughout the Old West like almost no other documents can. Additionally, many of these same regular army veterans, including the famed Buffalo Soldiers, applied for and received pensions for themselves or their widows and descendants. These files are similar to the more familiar Civil War pension files, many of which run to hundreds of pages. They often document ancestors’ lives in minute detail, including their physical health and their experience during service, including wounds received in battle. Military records are an invaluable source for tracing the path of any ancestors whose path west was facilitated by military service.

Land, census, and military records are but a few of the many sources that you can use to assist you in your quest to walk in your ancestors’ footsteps as they made their way through the wild, western lands of the American frontier.

Do you have ancestors that migrated westward? Have you hit brick walls when it comes to finding records of them? Contact Legacy Tree Genealogists for a free research package quote! Their genealogy experts can help you recover the stories of your ancestors that lie waiting in thousands of documents that still survive from that tumultuous, endlessly fascinating era. Exclusive Offer for Genealogy Gems readers: Receive $100 off a 20-hour research project using code GGP100.

Legacy Tree Genealogists is the world’s highest client-rated genealogy research firm. Founded in 2004, the company provides full-service genealogical research for clients worldwide, helping them discover their roots and personal history through records, narratives, and DNA. Based near the world’s largest family history library in downtown Salt Lake City, Utah, Legacy Tree has developed a network of professional researchers and archives around the globe. More information is available at https://www.legacytree.com.

I too have an ancestor in two 1850 censuses. My great great grandfather is listed in the Independence, Jackson, Missouri census with his wife and 3 children. He is also listed in Sacramento, Sacramento, California census.

The California census was taken very late that year.

I think he wasn’t in Missouri as 49er’s would have left before it was taken, as soon as the grass greened. His wife probably gave his name even tho he had already left.

I have his death record in Sacramento and even a copy of the funeral home record telling what he died of and what Dr. attended him. I also know where he is buried in a mass grave in Sacramento. Those people were buried elsewhere and they had to be moved.