The 1790 United States census was the first census taken after the establishment of the new country, so documenting ancestors’ presence at this historic time often inspires a sense of patriotism. However, locating those census entries can pose a few challenges. Use these five tips to conduct a more successful search in the 1790 census as well as in other documents.

Thank you to the experts at Legacy Tree Genealogists for this guest post!

1. Meet handwriting challenges head-on.

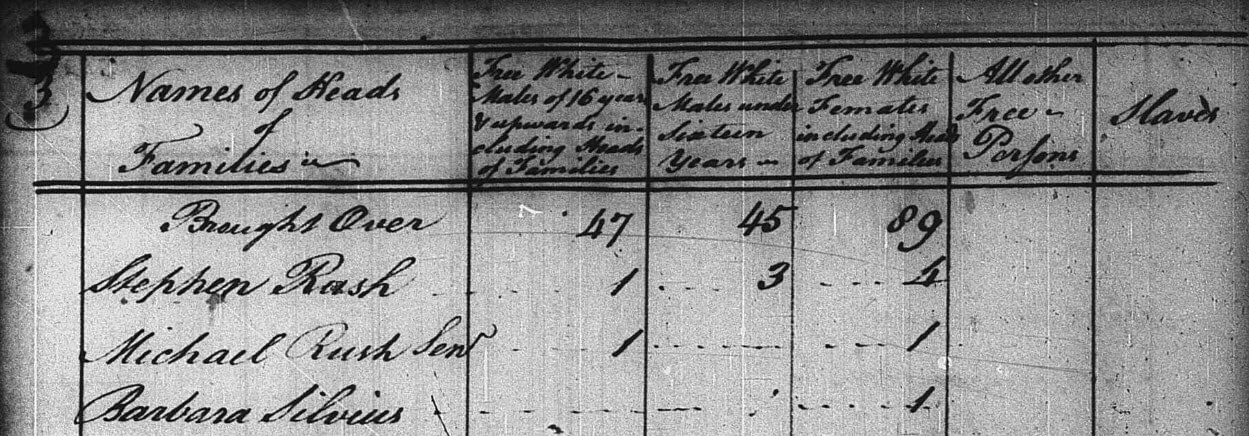

Handwriting from the 1790s often looks like a foreign language to modern eyes, including to people who helped index the census. The FamilySearch Wiki includes links to several videos and articles under the title “United States Handwriting.” Use these links to become familiar with the different writing styles in early American records. If your ancestor doesn’t seem to appear in the census index, look for creative spellings by the census taker.

Also, try looking for the name by substituting letters that might have been misread by the indexer. For instance, a search for Silas Sawdy initially turned up no results, even looking for Sandy, Lawdy, and Landy. The entry for “Silas Soddy” was finally located by going through the census page by page, but the indexer had read his name as Tilus Toddy.

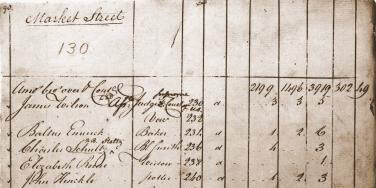

Image: 1790 Census, courtesy of FamilySearch.org

2. Know what is included in the 1790 U.S. Census.

The 1790 U.S. Census contains very limited information about the household members. Census entries were organized using the names of heads of households, with tick marks in different columns to indicate household members. There were only five questions asked about the individuals in each dwelling:

- The number of free white males under 16 years of age

- The number of free white males age 16 and upward

- The number of free white females

- The number of other free persons

- The number of slaves

The count could include visitors, servants, relatives, and of course, the members of the immediate family. Some children might have been working outside the home or were being cared for by others. In those instances, the children would have been enumerated in the household where they lived the day the census was taken. When the father in the family was deceased, a son would usually be listed as the head of household rather than the surviving widow, though some women were given that title. The oldest person was also not always listed as head of household, especially if elderly parents made their home with a younger family member.

3. Gather information about your ancestor’s family structure.

The 1790 census is not a stand-alone document. Learn as much as possible about your ancestor’s family and use this knowledge in conjunction with the census. Collect documentation from later censuses, town records, land dealings, wills, and local histories. When there are several possible matches in the 1790 census, focus first on those whose family structure most closely fits the target households. For example, if your ancestor had young sons in 1790 and there were several households in the area headed by men with the same name, it is easier to rule out the entries with no males under 16. Remember that the household numbers did not always reflect just the members of the family, so especially if there were more individuals in the household than expected, the entry may still be for your ancestor.

4. Locate the proper area for your search.

Use gazetteers and maps of the places your ancestors lived. Names of towns and counties, as well as their boundaries, fluctuated over time. The FamilySearch Wiki contains valuable information about the locations and dates of these changes, as do other online sources. It is vital to know that the 1790 census returns from Delaware, New Jersey, Virginia (including West Virginia), and Georgia, along with the territories of Kentucky and Tennessee were destroyed when the Capitol was burned in the War of 1812. Surviving records are from the present states of Maine (included as part of Massachusetts), New Hampshire, Vermont, New York, Pennsylvania, New York, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Maryland, North and South Carolina.

5. Research all the families in the area with the target surname and related surnames.

Once the ancestral town for the family has been determined, gather census records for all those in the area with that surname, moving outward to the county level, then the state. Especially if the surname is uncommon, it may be possible to find other documents to link these families together. Pay particular attention to families who live near each other who have known surname connections. For example, if two possible matches exist for Isaac Johnson but one is enumerated on the same page as Eli Garrick and the ancestral Isaac Johnson married a Garrick, that entry is more likely to be for the ancestor.

Though locating ancestors in the 1790 U.S. Census can be a challenge, this document can provide a valuable “puzzle piece” to create a complete picture of the family.

Legacy Tree Genealogists is a full-service genealogical research firm that helps clients worldwide discover their roots and personal history through records, narratives and DNA. Visit the Legacy Tree Genealogists website for a FREE consultation!

Exclusive Offer for Genealogy Gems readers: Receive $100 off a 20-hour research project using code GGP100.