by michaelstrauss | May 24, 2018 | 01 What's New, Holidays, Military

The history of Memorial Day–formerly Decoration Day–and what he will be doing to honor it are shared here by Military Minutes contributor Michael Strauss. We also give you quick links to more free family history articles on researching your ancestors who gave the ultimate sacrifice on the battlefield.

(Image right: Gravesite in Oak Woods Cemetery, Chicago, IL. Decoration Day, 1927. Photo: Chicago Daily News)

History of Memorial Day

In 1865, just after the close of the Civil War, a local druggist in Waterloo, New York suggested placing flowers on the graves of fallen soldiers in his community.

The following year, another area resident, General John B. Murray, led the small village in putting flags at half-mast and decorating the gravestones of soldiers buried in the town’s three cemeteries. They repeated their efforts the following year. Many other communities in both the North and South also honored their war dead during this time period.

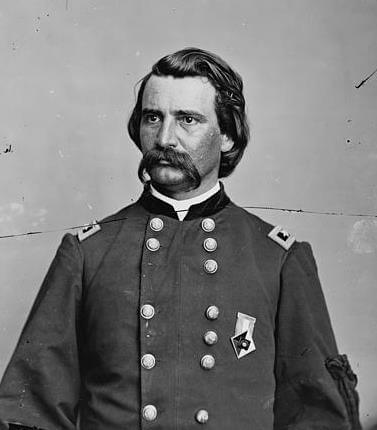

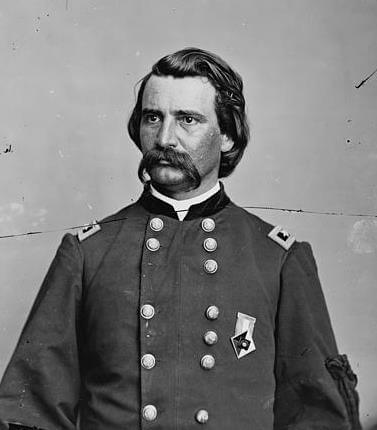

General John A. “Black Jack” Logan spearheaded the idea of a national day of remembrance for fallen Civil War soldiers in 1868. Logan, a former Union General, was the National Commander of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), which constituted living veterans of the war. On May 5, 1868, the GAR issued General Order No. 11 to designate May 30, 1868 as the day to decorate and commemorate the graves of fallen comrades of the late Civil War.

The wording of the order is very specific: “Let us then at the time appointed gather around their sacred remains and garland them with choicest flowers of springtime…Let us raise above them the dear old flag they saved from dishonor…in this solemn presence renew our pledge to aid and assist those whom they have left among us…the soldier’s and sailor’s widow and orphan.” This order later became known as the “Memorial Day Order” and can be read on the website of the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs as part of the National Cemetery Association.

On this date at Arlington National Cemetery, more than 20,000 gravestones of both Union and Confederate veterans were remembered. General James A. Garfield (who later became President of the United States) and other political leaders spoke to an audience of more than 5,000 persons. In following years, May 30th became known as Decoration Day, a national day of remembrance of the Civil War dead.

General John A. “Black Jack” Logan. Library of Congress image.

After the end of World War I in 1918, the scope of Decoration Day expanded to include all war dead since the Revolutionary War. The name gradually gave way to “Memorial Day,” a term first used in 1882 that didn’t become more generally accepted until after the end of World War II. A 1968 Act of the United States Congress, which went into effect in 1971, formally calendared the dates of several national holidays, including Labor Day, Veterans Day, and Memorial Day—the latter to be held in perpetuity on the last Monday in May. (Veterans Day, honoring all veterans who served rather than just our war dead, is held on November 11th.)

1917 poster, Library of Congress image.

Interestingly, not every part of the United States fully supported Decoration Day. The Civil War created divisions even in peacetime, long after the guns fell silent in 1865. A number of Southern states have over the years honored their own Confederate dead on specific dates. In Mississippi, for example, they remember Memorial Day the last Monday of April. Both North Carolina and South Carolina observe this date on May 10th. In Virginia, the last Monday of May is observed as with most of the country, but it is often called Confederate Memorial Day.

For a little more history (and some great historical re-enactment footage), enjoy this quick video.

How I will be honoring Memorial Day

Regardless of the name given this holiday, on Memorial Day here in Utah I will remember and honor those who sacrificed so much for our country by attending a free public event at Camp Floyd. I will be wearing my Civil War uniform with other members of the Utah Living History Association as we recreate and experience camp life; drill; and fire our period weapons to remember when the camp was occupied by the Union Army from 1858-1861. I am the second person in the left in this 2016 photo from the Utah Living History Association. We strive for historical accuracy in our representation of the men stationed at this camp in the years immediately preceding the Civil War. (With the start of the war, the camp was abandoned and the men stationed here moved back East to the fighting. Next to the museum at the camp sits a small rural cemetery to honor the burials of 85 men who died from 1857-1861 who were stationed at the camp while serving with the United States Army.)

Memorial Day isn’t just about remembering those soldiers who died in battle, but about honoring all veterans who have honored us with service. We give this honor—regardless of sectional differences—to those who lost their lives during both wartime and peacetime periods.

Michael Strauss, AG is the principal owner of Genealogy Research Network and an Accredited Genealogist since 1995. He is a native of Pennsylvania and a resident of Utah and has been an avid genealogist for more than 30 years. Strauss holds a BA in History and is a United States Coast Guard veteran.

by michaelstrauss | Mar 19, 2018 | 01 What's New, Military, United States |

Our female ancestors in the U.S. military had to serve incognito. Only in the 20th century have women served openly and with greater frequency—and in combat roles. Here, military expert Michael Strauss salutes the women who have bravely served, including one in his own family.

In times of emergency, men primarily bore arms in U.S. history. However, not all women filled the traditional roles relegated to them by society. From the days of the Revolutionary War, any woman who chose to fight would have to disguise herself as a man. This was the case of Deborah Sampson, who served under the alias of Robert Shirtliffe until she was discovered and discharged from the Army.

Other women, such as one named Margaret Corbin, were camp followers and served by cleaning and cooking. During the battle at Fort Washington in New York, her husband John was mortally wounded while manning his artillery piece. Margaret took his place on the gun, continuing the fight against the British. For both women their sacrifice was not forgotten; each was awarded pensions from the Government based on their military service–although Corbin received only half of the pension allowance because she was a woman.

During the Civil War, women again sought to join the ranks of the military. Take, for example, Jennie Irene Hodgers, a native of Ireland who enlisted in Company G of the 95th Illinois Infantry, where she served using the alias of Albert Cashier. Her identity was kept secret during the entire war. It wasn’t until she was much older—in 1911—that a doctor discovered she was actually a woman.

The turn of the twentieth century had women more accepted in the ranks of the Army. The establishment of the Nursing Corps in 1901 saw the first large scale enlistment of women. Still later in World War II was the forming of the Woman’s Auxiliary Corps (WAC) and the Women Air Force Service Pilots (WASPS) who flew to great heights.

The other military branches took nearly as long to accept women in their ranks. The Navy in 1908 established the Nursing Corp with the first enlistments of women. In 1918, Opha Johnson became one of the first women to put on the uniform of the United States Marine. Twin Sisters Genevieve and Lucille Baker were the first women to join the Coast Guard during in 1917. Like the Army’s organizations in 1942 the Naval Women’s Reserve (known as the WAVES), was followed shortly by the Coast Guard Women’s Reserve (known as the SPARS).

Many of these women were relegated to nursing and clerical positions, with very little opportunity for actual combat experience. It wasn’t until World War II that larger numbers of women were sent into combat. In 1948, President Harry Truman signed the Women’s Armed Service Integration Act that allowed for a permanent presence of women in all of the military branches, a tradition that still holds strong. Today, the descendants of these early pioneers can look back to learn from their past experiences by striving for continued service to the United States for future generations.

Women in U.S. military history: My family

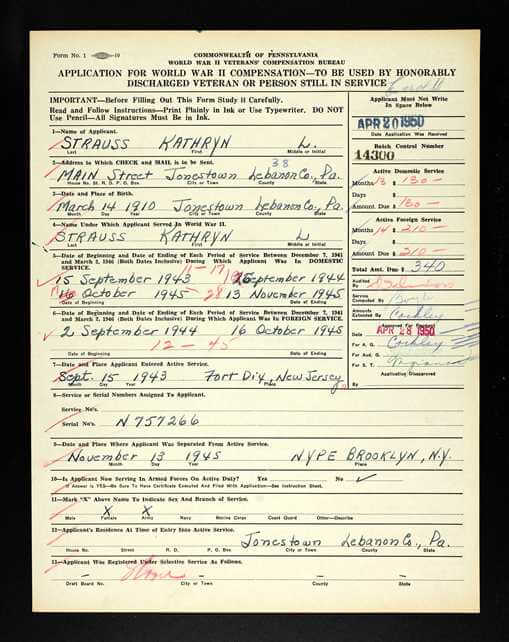

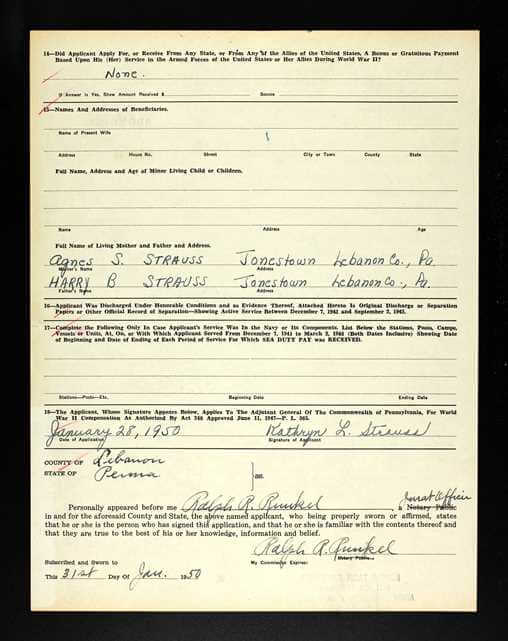

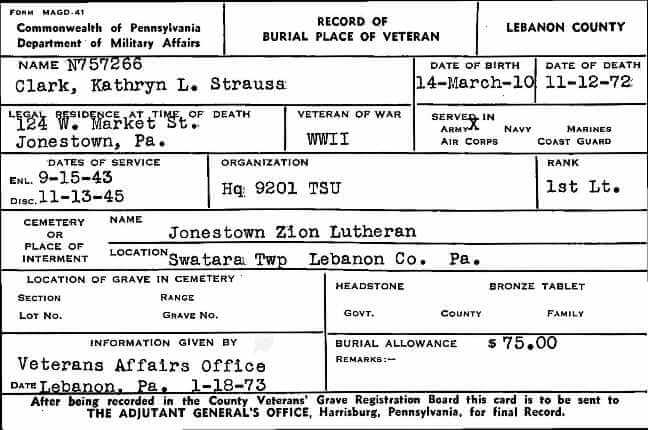

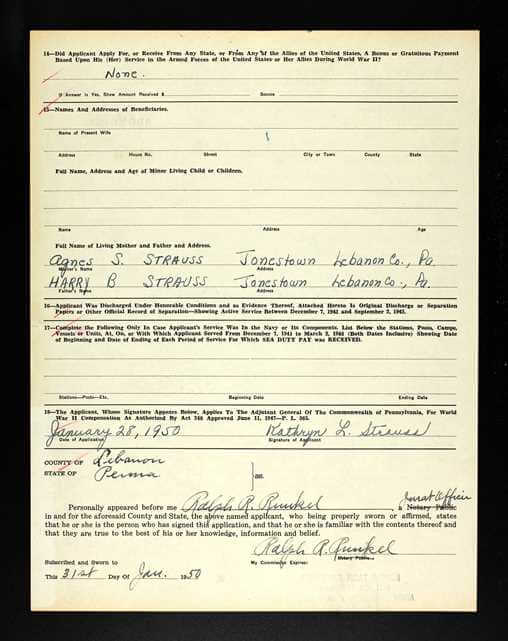

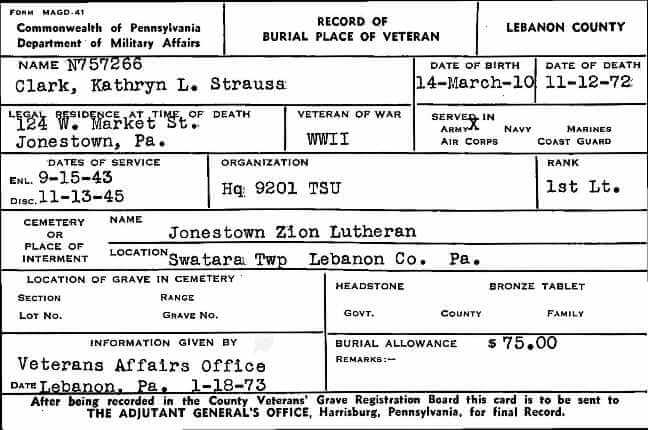

Recently I shared a profile of my relative Russell Strauss, who served in the Navy during World War II. One of his two Sisters also served during the war. His younger sibling Kathryn Strauss served in the United States Army.

Kathryn graduated in 1930 from the University of Pennsylvania Nursing School at the age of twenty years old. She worked in the University Hospital in Philadelphia and later in the Public Health Department in Vineland, New Jersey until the start of World War II.

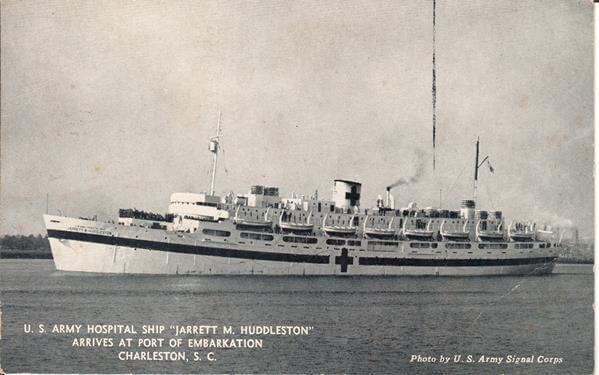

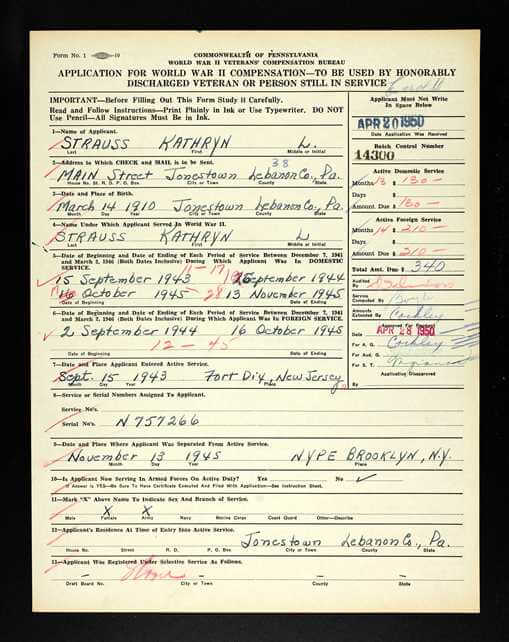

Kathryn joined the United States Army on September 15, 1943 at Fort Dix, New Jersey. She was commissioned a 1st Lieutenant in the Army Nursing Corps. Kathryn served both in the United States and overseas. From her enlistment date until September 2, 1944, she was stationed in New Jersey and New York. She served overseas stationed aboard the S.S. Jarrett Huddlston, a hospital ship on which she made 34 trips across the Atlantic Ocean.

Kathryn afterwards was sent back to the United States where she was discharged on November 13, 1945 in Brooklyn, New York. She returned to Pennsylvania, where she continued to work in the nursing field until her death on November 12, 1972 in Jonestown. The above photograph of her in uniform and postcard of her hospital ship were passed down to me through my relatives.

I located her application for compensation from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 1950 on Ancestry.com. It gives details about her military service during World War II (see below). This personal story along with genealogy documents that I was able to locate shared how women in my family served alongside some of the men during war and how their place in history is reserved for honor.

Keep watching this blog for an upcoming post about unique research resources for finding your female ancestors in U.S. military records. Meanwhile, here’s something fun to read:

Genealogy Gems Book Club Recommendation: Story of a WASP

Want to read a fun and fascinating novel about women of the Women Air Force Service Pilots (WASPS)? Genealogy Gems Book Club Guru Sunny Morton highly recommends The All-Girl Filling Station’s Last Reunion, in which a lively, lovable Southern lady searches for her biological family and finds women of the WASPs. The story is by internationally-acclaimed novelist Fannie Flagg, a Genealogy Gems Book Club author who appeared on the Genealogy Gems Premium Podcast Episode #148. Want to browse more fantastic Genealogy Gems Book Club picks? Click here!

Michael Strauss, AG is the principal owner of Genealogy Research Network and an Accredited Genealogist since 1995. He is a native of Pennsylvania and a resident of Utah and has been an avid genealogist for more than 30 years. Strauss holds a BA in History and is a United States Coast Guard veteran.

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links and Genealogy Gems will be compensated if you make a purchase after clicking on these links (at no additional cost to you). Thank you for supporting Genealogy Gems!

by michaelstrauss | Jan 22, 2018 | 01 What's New, Military, United States

Military terminology for genealogists: What’s the difference between “regulars,” “volunteers” and “militia” in your U.S. ancestors’ military service records? It matters! Researching the records of each–and what you find–may be very different. Expert Michael Strauss explains here.

Military terminology for genealogists (and why it matters)

If you’ve looked through your U.S. ancestors’ military records, you’ve likely come across terms like Regulars, Volunteers, and Militia. What do those terms mean? You’ll want to know because the records were different and so were their terms of service. Also, you may come across relatives who served in more than one capacity.

Regulars were those men who enlisted for a specific period of time as part of the standing army. These men could have enlisted during a war period or peacetime. During the colonial period, they may have been recorded with other names, as either the Continental Line or part of the Flying Camp. The latter were men who served directly under General George Washington. Look for service records of Regulars at the National Archives. (Click here for a free download: Military Service Records at the National Archives by Trevor K. Plante.)

Volunteers were men who served during wartime or any period of emergency whose service was considered to be in the interest of the Federal Government. Recorded from the Revolutionary War onward, these men at that time might also be listed early on as “Associators.” Not to be confused with militia, Volunteers were not subject to fines for non-service. Like the Regulars, records of volunteers’ service are also found at the National Archives.

(A good example of the difference between Regulars and Volunteers can be found during the Spanish American War of 1898. During the war, there was a Regular Army 1st U.S. Cavalry that served alongside the Volunteer 1st U.S. Cavalry. The latter was known as the “Rough Riders,” led by Colonel Theodore Roosevelt.)

The militia was organized initially by colonial, then state and even county governments. (Pennsylvania’s colonial militia is a great example of typical colonial militia laws, rules, and regulations, and parent organizations; click here to read an article about the Pennsylvania militia.) Militia was generally men called up for limited military duty between the ages of 17-60 as needed for the common defense. They were often required to serve for a period of time that was based on the militia laws on the books. The men were subject to fines or penalties for non-service. Records of militia are going to be found at your local or state archives. (Click here for a directory of state archives in the U.S.)

Example: He was a Volunteer and a Regular

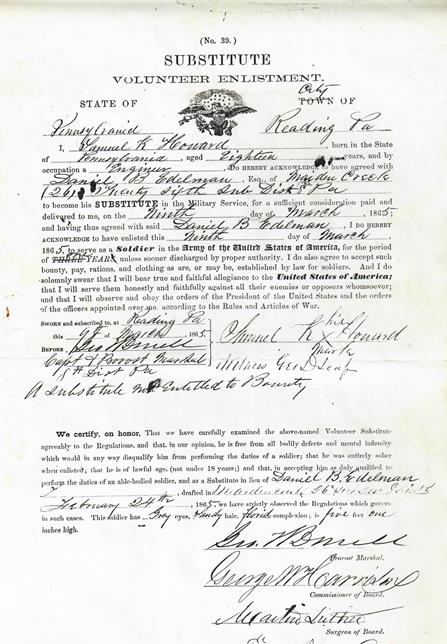

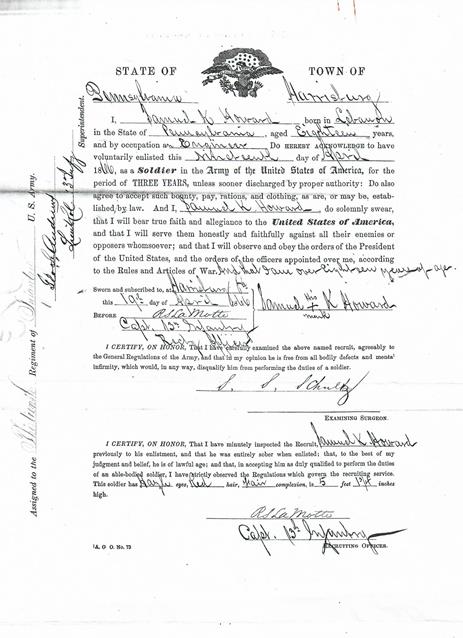

My ancestor, Samuel Howard, served during the Civil War. Because of his age he wasn’t able to enlist until 1865, when he turned 18.

- He was first a Volunteer soldier, who served as a substitute for another man who was drafted.

- After his discharge, he enlisted in the Regular Army in 1866. He was assigned to the 13th U.S. Infantry, where he served one month before deserting at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri.

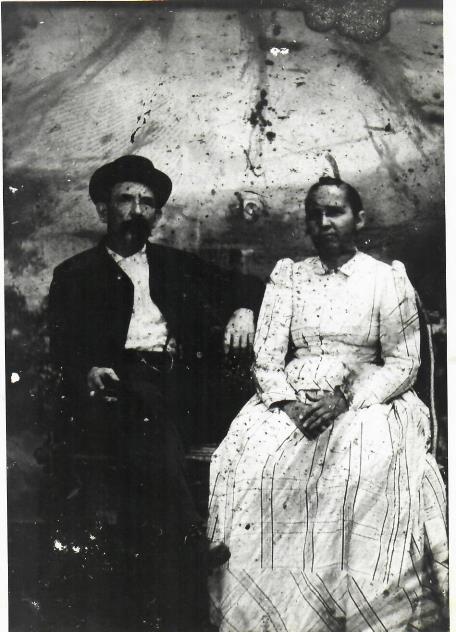

- Samuel was married in 1867 (this may have some relevance to his decision to leave the military). He lived in Pennsylvania from the end of the war until his death in 1913. He is shown here in this 1876 tintype photograph in Lebanon, PA.

Both his Volunteer and Regular Army enlistment forms are shown below. The forms look very similar, as each contains common information asked of a typical recruit. However, they are decidedly different as the one covers his Civil War service and the other his post-war service when he joined the regular Army after the men who served during the war would have been discharged.

Take-home point for you: I believe the key to finding your ancestors, whether they served in the Regulars, were Volunteers or Militiaman, is to look at not only federal records but also search your state records. The latter may be the only place you find proof of military service. Samuel Howard’s Regular Army military service, although brief, was completely unknown to me until a couple of years ago. When he applied for his Civil War pension, which was granted to him, he never mentioned his Regular army service.

And keep learning more helpful military terminology for genealogists! Click here for resources on military acronyms, abbreviations, and dictionaries from the National Archives that can help that you research exactly how your ancestors served.

Michael Strauss, AG is the principal owner of Genealogy Research Network and an Accredited Genealogist since 1995. He is a native of Pennsylvania and a resident of Utah and has been an avid genealogist for more than 30 years. Strauss holds a BA in History and is a United States Coast Guard veteran.

by michaelstrauss | Dec 6, 2017 | 01 What's New, Military |

Official Military Personnel Files (OMPFs) are 20th and 21st U.S. military records for conflicts such as WWI, WWII, and beyond. OMPFs are packed with great genealogy clues, but millions were destroyed by a 1973 fire. Here’s how to find what records still remain, and what you might find if your relative’s OMPF went up in flames.

What are Official Military Personnel Files?

If your ancestor served in the U.S. military during the 20th or 21st century, related service records are called Official Military Personnel Files (OMPFs), or sometimes “201 files,” named after the brown file folder that holds them. These are available for each of the military branches: Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines, and Coast Guard. They are generally held at the National Personnel Record Center in St. Louis, Missouri. (Exceptions for veterans discharged since 1995 may be at other government offices.)

According to the National Archives, Official Military Personnel Files are “primarily an administrative record, containing information about the subject’s service history such as: date and type of enlistment/appointment; duty stations and assignments; training, qualifications, performance; awards and decorations received; disciplinary actions; insurance; emergency data; administrative remarks; date and type of separation/discharge/retirement; and other personnel actions.” The level of detail in complete files make them invaluable genealogical records.

How to Access Official Military Personnel Files

On July 12, 1973, a disastrous fire ravaged the building where the OMPFs were housed. Between 16 and 18 million personnel files were destroyed or damaged; these affected names alphabetically after James E. Hubbard. It was a serious loss for two particular branches of the military:

- Army Personnel discharged 1912-1960: 80% Loss (4 in every 5 files).

- Air Force Personnel discharged 1947-1964: 75% Loss (3 in every 4 files). (Remember: the Air Force wasn’t officially organized until September 14, 1947. Before this date Air Force records were part of the United States Army Air Corps, then part of the U.S. Army.)

The Navy, Marines, and Coast Guard records were largely unaffected by the fire.

Surviving OMPFs and reconstructed records relating to destroyed files are considered to be archival (or open to researchers without restrictions) 62 years after the date of discharge. This is a rolling date, so discharge dates of 1955 and earlier are open to the public. In 2018, that date will change to 1956, and so on. More recent records are considered non-archival and subject to restrictions; only the veteran or next-of-kin have full access to the files.

You can access Official Military Personnel Files in three ways:

1. Go to St. Louis in person. Appointments are recommended, as research space is limited. Click here for information about requesting an appointment, the availability of records, copy fees, and hours of operation.

2. Employ an independent researcher. Click here for the National Archives’ list of researchers.

3. Request records by mail. Here’s a link to the online portal for requesting these records; here’s a direct link to the PDF format of Standard Form 180, which you can print and mail in.

My grandfather’s OMPF: What survived?

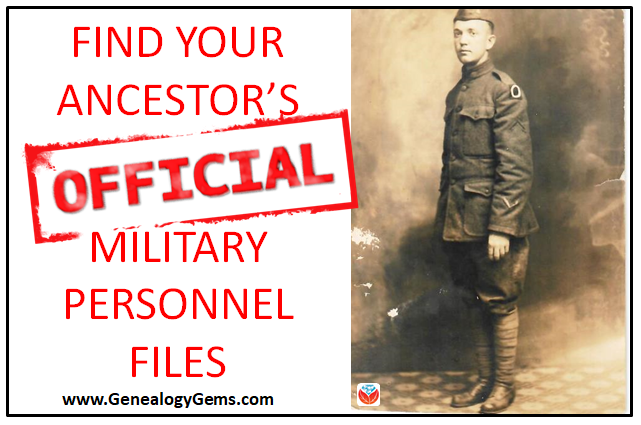

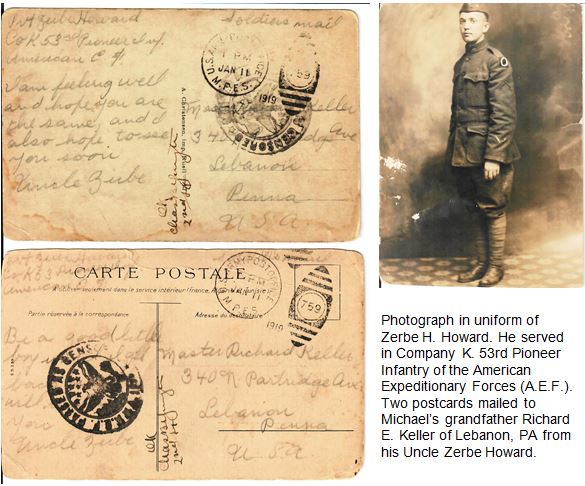

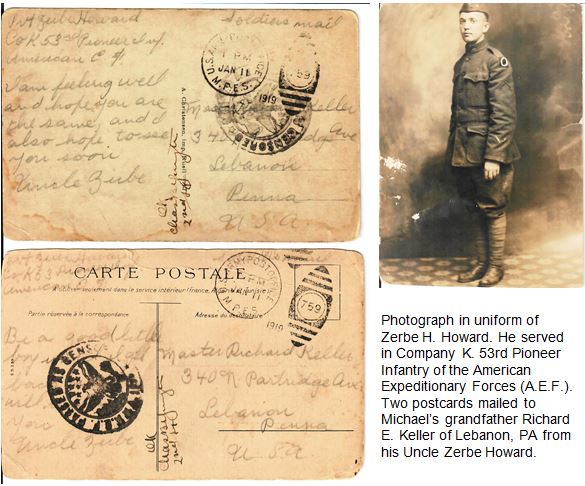

I didn’t fully grasp how many records were lost in the fire in 1973 until I ordered a record of one of my family members. When my grandfather Richard Keller was a small child, he received postcards from his great Uncle Zerbe Howard: I remember him. He died when I was 10 years old. Zerbe served during World War I and was a resident of Lebanon, PA.

I have in my possession the 2 postcards sent my grandfather that listed his name, rank, and military unit. I ordered his file which took several months, and when it arrived I expected it to be full of information. Unfortunately, his file was completely destroyed.

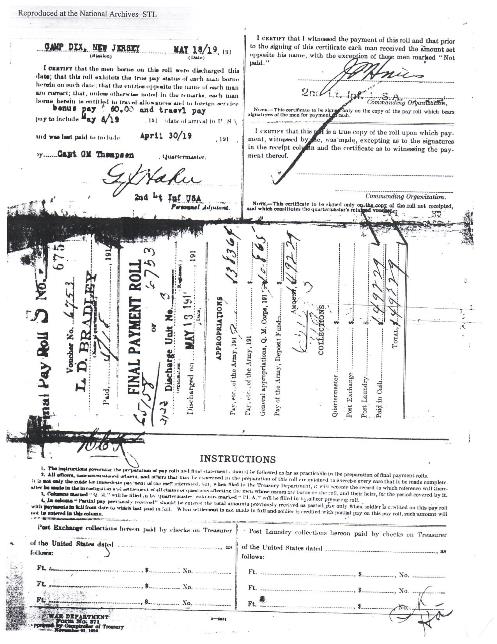

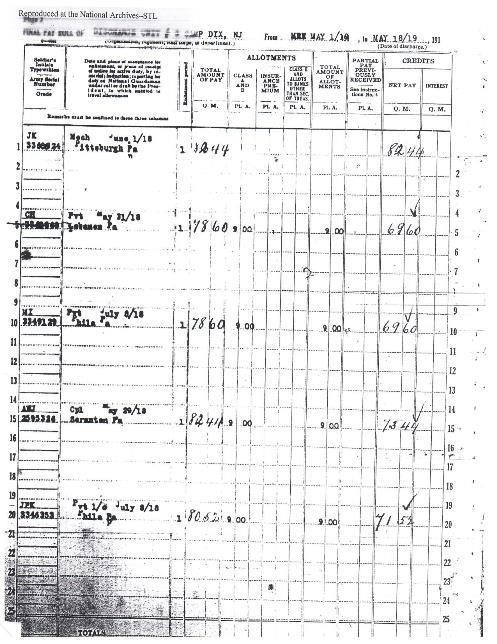

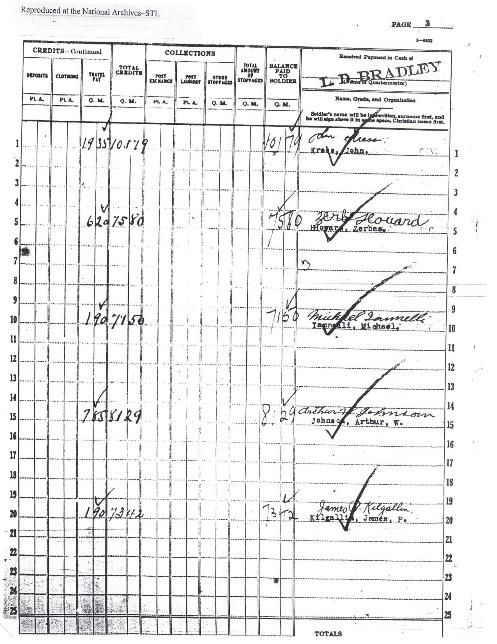

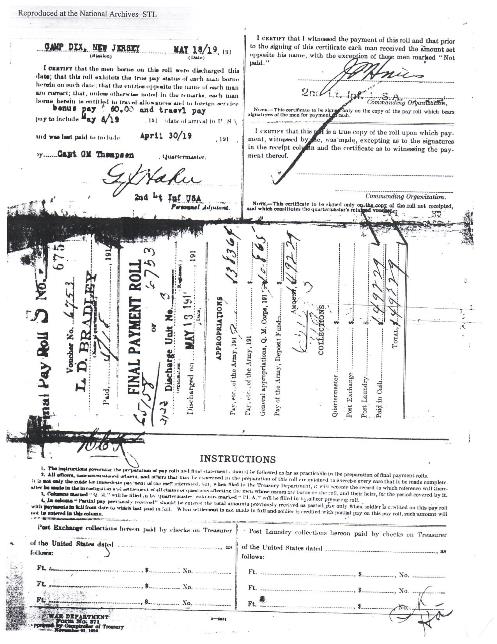

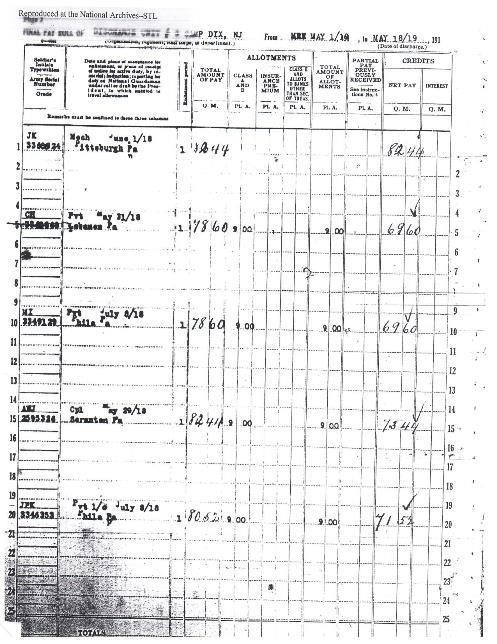

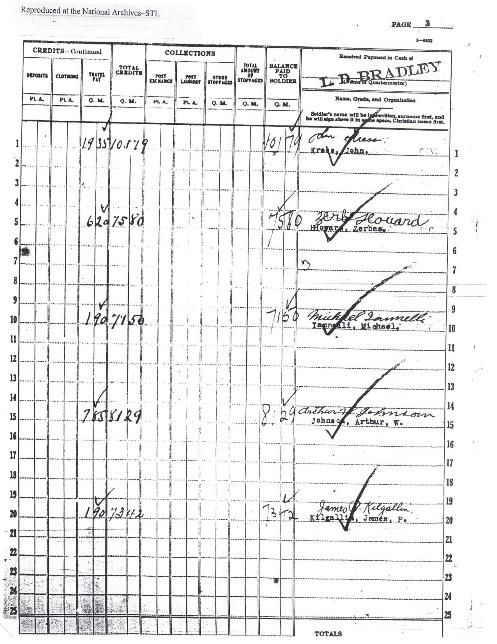

The only reconstructed records located were three pages recording him on a final payment roll with other men from his unit. Here’s an image of that record, which seems so sparse compared to what that original OMPF may have contained:

This final payment roll from Camp Dix, New Jersey is dated from April 1918 to May of 1919. It reveals that the soldiers on this roll were discharged on this date, that they were entitled to travel allowance and foreign service bonus pay of $60 and what their individual payments were. Zerbe even appears to have signed the record in his own scrawling handwriting. While it may be discouraging to have such limited information available due to the 1973 fire, it’s still worth pulling records such as these to track your military ancestors.

The National Personnel Record Center now has other records available to researchers to help fill in some of the gaps. For example, the Army filed Morning Reports, organized by unit. I also found local records in Pennsylvania that were not in the hands of the federal government. Listen to the free Genealogy Gems Podcast or come back to this blog for future tips on researching your 20th-century U.S. relatives’ military service.

Looking for 19th century US military records?

If your ancestor served in the military during the 1800s or earlier, you’ll want to look for his Compiled Military Service Records at the National Archives in Washington, DC. The exact dates for each military branch vary in years accordingly. Click here to learn more about those.

If your ancestor served in the military during the 1800s or earlier, you’ll want to look for his Compiled Military Service Records at the National Archives in Washington, DC. The exact dates for each military branch vary in years accordingly. Click here to learn more about those.

For more ongoing training in tracing your military ancestors, tune in to the free Genealogy Gems Podcastand listen for my segment, “Military Minutes.”