Blog

Resolving Three Common Conflicting Evidence Problems in Genealogy

Resolving conflicting evidence in genealogy research is sometimes difficult. Some types of conflicting evidence we come across are common. Here are some tips to resolving three of the most common conflicting records and why they exist.

I joke about our recent “cookie incident” here at home. No one wanted to fess up to who ate all the cookies, but it didn’t take long to evaluate the evidence and come up with the culprit. The trail of crumbs, the height at which the cookies were stored, and who was home at the time, were just a few of the ways in which I came to a sound conclusion.

As genealogists, we have to weigh disagreeing or conflicting evidence all the time. Maybe you have two records giving two different birth dates for a great great grandmother. Whatever the conflict, here are some tips to resolving three of the most common conflicts and why they exist.

Item 1: Resolving a Birth Date Conflict

I have found numerous birth date conflicts in my personal family history. Some reasons may include:

- Transcription errors

- Delayed recording

- Lying to protect the couple from embarrassment of a pre-marriage pregnancy

- Engraving mistake on the tombstone

- To avoid a military draft

These are just a few of the many reasons why you may find a conflicting birth date. Resolving a birth date conflict, or any genealogical data conflict, may be possible by remembering the following:

The record recorded nearest the time of the event, by those who have first-hand knowledge, is typically considered the most reliable source.

Here’s an example. Nancy Blevins Witt has two possible birth dates. Using her death record, we can only calculate a birth date based on her age-at-death given in years, months, and days. That calculated birth date would be 19 Nov 1890. However, the date of birth recorded on the 1900 U.S. Federal Census is October 1890, and we were never able to find a birth record. Which birth month is likely correct, October or November?

To make this determination, we will need to consider the following:

1. A death record has an informant. Who was the informant of Nancy’s death record? Did this person have first-hand knowledge of her birth, such as a parent? In this case, the informant was her uncle. There is no way to know if the uncle was present at the time of her birth, but he was alive at the time.

2. Who was the likely informant of the 1900 census? Was that a person with first-hand knowledge of Nancy’s date of birth? We can’t be absolutely sure, but we could suppose that Nancy’s mother was the one who gave the census taker that information. Since the mother was obviously present at the time of Nancy’s birth, we would consider her a reliable witness to the event of Nancy’s birth.

3. Do any of these informants have a reason to lie? Is there something, like money, to be gained by providing a certain birth date? The answer is no.

We can say that the likely accurate date of birth for Nancy is October 1890. Of course, we want to make note of both the records and the discrepancies in our personal database and remember that it is always possible a new piece of evidence will pop up that makes us re-evaluate this assumption.

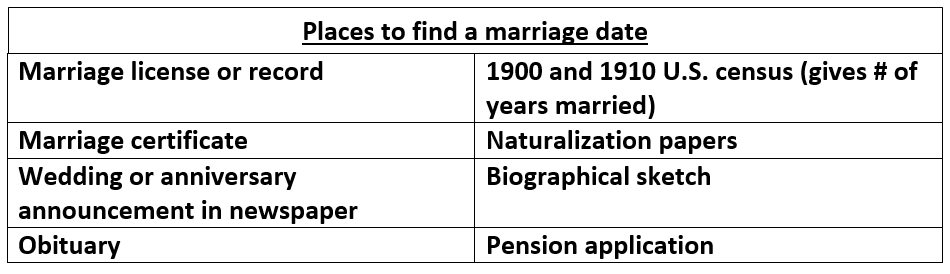

Item 2: Resolving a Marriage Date Conflict

Marriage date conflicts can be found for a variety of reasons as well. Some of these reasons may include:

- Transcription error

- Delayed recording

- Lying to avoid an embarrassing situation

- Altering the date for the benefit of widows pension

Again, these are just a few of the reasons for a marriage date conflict.

In this next example, John and Eliza are said to have married about 1857. Unfortunately, no actual marriage record was ever found.

There are however, two sources for a marriage date. Both of these sources are found in the War of 1812 Pension Application Files which was viewed online at Fold3.com. A War of 1812 Pension Application is a great place to find marriage information. The widow would have needed to prove that she was indeed the widow of the veteran before being able to receive her pension. Widows sometimes supplied actual marriage certificates, or like Eliza, they may have included affidavits instead.

This pension file for Eliza contained two documents, the first of which was an affidavit given by Eliza herself stating that she and “Jackson Cole” were married in March 1857 in Harlan, Kentucky by Stephen Daniel. Sadly, throughout the application, Eliza changes dates, ages, and names making us wary of whether her information is accurate. She had also been denied pension once before, and this was her second attempt. Because this is a pension and dealt with money allocation, and because she had been denied before, there is a reason for her to lie or fudge dates and details of the facts to meet certain criteria. We will want to take this into consideration. The second document is an affidavit from Stephen Daniel who states he married the couple in 1854.

Now, we want to further evaluate the two sources.

- Stephen has nothing to gain (i.e. money, land, etc.)

- Both Eliza and Stephen had first-hand knowledge of the event.

- They were both remembering this marriage event and testifying to it almost 45 years later.

- Stephen was a minister who married perhaps hundreds of couples.

- Eliza only ever married once.

Who do you think would most likely remember the date of marriage? If you said Eliza, I think you are right. Further, the fact that Eliza had her first child about 1857 is also a strong indication that a marriage had taken place fairly recently. Based on all these reasons, we could assume the most likely date of marriage was March 1857.

Item 3: Resolving a Death Date Conflict

Reasons for conflicting death dates may include:

- Transcription error

- Engraving mistake on the tombstone

- Delayed recording

- Misprint in a newspaper obituary or biographical sketch

An example of a conflicting death date might be that an obituary says the person died on 20 February 1899, but the death record and tombstone give the date as 19 Feb 1899. We all know that newspapers are notorious for misprints. Further, a death record indicating the death date of 20 February 1899 is a record typically made on or near the date of death. This is typically when information is most fresh in the minds of the informants. A newspaper article, however, could have been printed days or even weeks later.

More Gems on Conflicting Evidence in Genealogy and Using the Genealogical Proof Standard

Whatever the conflict, you can typically use these practices to come to a sound conclusion. Oh! And by the way, have you ever heard of using the “GPS?” We aren’t talking about the little device that tells you how to get to that really cool new restaurant. We are talking about the Genealogical Proof Standard. Resolving conflicting evidence is just one of the components of the GPS. To learn more about this high standard, listen to podcast episode #23: Using the Genealogical Proof Standard.

[1] “1913: Statewide Flood,” article online, Ohio History Connection, accessed 27 Dec 2016.

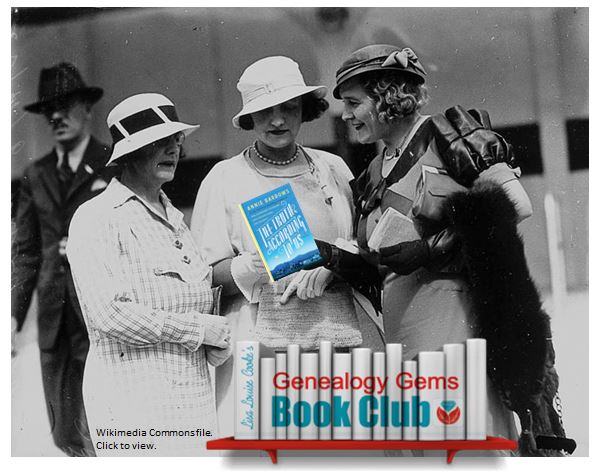

Family Secrets, History and Love in the Great Depression: Genealogy Gems Book Club Pick

Our new Genealogy Gems Book Club pick takes you into the Great Depression with a young socialite’s WPA project to capture the history of a small West Virginia town. She finds drama, contradicting versions of the past and unexpected romance. Enjoy this novel by an internationally best-selling author!

Our new Genealogy Gems Book Club pick takes you into the Great Depression with a young socialite’s WPA project to capture the history of a small West Virginia town. She finds drama, contradicting versions of the past and unexpected romance. Enjoy this novel by an internationally best-selling author!

It’s the summer of 1938. Wealthy young Layla Beck’s big problem is not the Great Depression: it’s her father’s orders to marry a man she despises. She rebels, and suddenly finds herself on the dole. A Works Progress Administration assignment lands her in Macedonia, West Virginia, where she’s to write its history. As she starts asking questions about the town’s past, she is drawn into the secrets of the family she’s staying with—and to a certain handsome member of that family. She and two of those family members take turns narrating the story from different points of view, exploring the theme that historical truth, like beauty, is often in the eye of the beholder.

It’s the summer of 1938. Wealthy young Layla Beck’s big problem is not the Great Depression: it’s her father’s orders to marry a man she despises. She rebels, and suddenly finds herself on the dole. A Works Progress Administration assignment lands her in Macedonia, West Virginia, where she’s to write its history. As she starts asking questions about the town’s past, she is drawn into the secrets of the family she’s staying with—and to a certain handsome member of that family. She and two of those family members take turns narrating the story from different points of view, exploring the theme that historical truth, like beauty, is often in the eye of the beholder.

That’s a nutshell version of our new Genealogy Gems Book Club featured title, The Truth According to Us by internationally best-selling author Annie Barrows.  It’s available in print and on Kindle formats: click above to purchase. (Thanks for using this link: your purchase supports free content on the Genealogy Gems podcast and blog.)

It’s available in print and on Kindle formats: click above to purchase. (Thanks for using this link: your purchase supports free content on the Genealogy Gems podcast and blog.)

Annie will join us in the March 2017 Genealogy Gems Premium Podcast for an exclusive interview. That’s a members-only podcast; everyone else can catch a meaty excerpt in the March episode of the free Genealogy Gems Podcast. Between now and then, watch our blog for related posts on The Truth According to Us and the Great Depression–including genealogical records produced by the WPA.

Once you’ve enjoyed The Truth According to Us, I heartily recommend you curl up with Annie’s previous novel, The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society. Watch a trailer for that book here:

Her popular Ivy and Bean children’s book series is also an international best-selling series, and my daughter Seneca gives it two thumbs up!

Click here to see more Genealogy Gems Book Club selections and how you can listen to Lisa’s upcoming exclusive conversation with author Annie Barrows about The Truth According to Us.

Click here to see more Genealogy Gems Book Club selections and how you can listen to Lisa’s upcoming exclusive conversation with author Annie Barrows about The Truth According to Us.

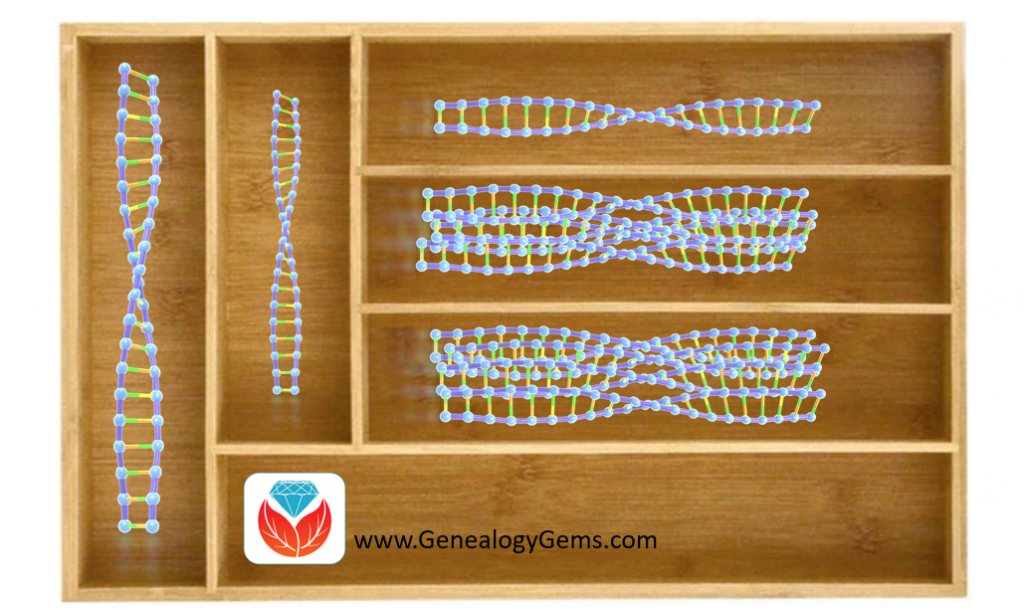

Organize DNA Matches in Your DNA “Drawer”

Organize DNA matches with this innovative approach. If you are feeling overwhelmed with your DNA results, you are not alone. Learning to organize your DNA matches in an effective way will not only keep your head from spinning, but will help you hone in on possible matches that will break down brick walls. Here’s the scoop from Your DNA Guide, Diahan Southard.

I can tell whose turn it was to unload the dishwasher by the state of the silverware drawer. If either of the boys have done it (ages 13 and 11,) the forks are haphazardly in a jumble, the spoon stack has overflowed into the knife section, and the measuring spoons are nowhere to be found. If, on the other hand, it was my daughter (age 8,) everything is perfectly in order. Not only are all the forks where they belong, but the small forks and the large forks have been separated into their own piles and the measuring spoons are nestled neatly in size order.

Organize Your Imaginary DNA Drawer

Regardless of the state of your own silverware drawer, it is clear that most of us need some sort of direction to effective organize DNA matches. It entails more than just lining them up into nice categories like Mom’s side vs. Dad’s side, or known connections vs. unknown connections. To organize DNA matches, you really need to make a plan for their use. Good organization for your test results can help you reveal or refine your genealogical goals and help determine your next steps.

Step 1: Download your raw data. The very first step is to download your raw data from your testing company and store it somewhere on your own computer. See these instructions on my website if you need help.

Step 2: Identify and organize DNA matches. Now, we can get to the match list. One common situation for those of you who have several generations of ancestors in the United States, is that you may have ancestors that seem to have produced a lot of descendants. These descendants may have caught the DNA testing vision and this can be like your overflowing spoon stack! All these matches may be obscuring some valuable matches. Identifying and putting those known matches in their proper context can help you identify the valuable matches that may lead to clues about the descendant lines of your known ancestral couple.

In my Organizing Your DNA Matches quick sheet, I outline a process for identifying and drawing out the genetic and genealogical relationships of these known connections. Then, it is easier to verify your genetic connection is aligned with your genealogy paper trail and spot areas that might need more research.

This same idea of plotting the relationships of your matches to each other can also be employed as you are looking to break down brick walls in your family tree, or even in cases of adoption. The key to identifying unknowns is determining the relationships of your matches to each other.

Step 3: See the relationship between genetics, surnames, and locations. Another helpful tool is a trick I learned from our very own Lisa Louise Cooke–that is Google Earth. Have you ever tried to use Google Earth to help you in your genetic genealogy? Remember, the common ancestor between you and your match has three things that connect you to them: their genetics, surnames, and locations. We know the genetics is working because they show up on your match list. But often times you cannot see a shared surname among your matches. By plotting their locations in the free Google Earth, kind of like separating the big forks from the little forks, you might be able to recognize a shared location that would identify which line you should investigate for a shared connection.

So, what are you waiting for? Line up those spoons and separate the big forks from the little forks! Your organizing efforts may just reveal a family of measuring spoons, all lined up and waiting to be added to your family history.

More on Working with DNA Matches

How to Get Started with Using DNA for Family History

Confused by Your AncestryDNA Matches? Read This Post

New AncestryDNA Common Matches Tool: Love It!