Genealogy Research Techniques for Finding Your Free People of Color

Not all people of color were enslaved prior to the emancipation. In fact, many were freed long before that. Researching free people of color can be quite complex. Tracing my own family line (who were free people of color) continues to be a real learning process for me. However, don’t let the challenges deter you from exploring this rich part of your heritage. In this “Getting Started” post, we discuss the manumission process, “negro registers,” and more for tracing your free people of color.

Who are Free People of Color?

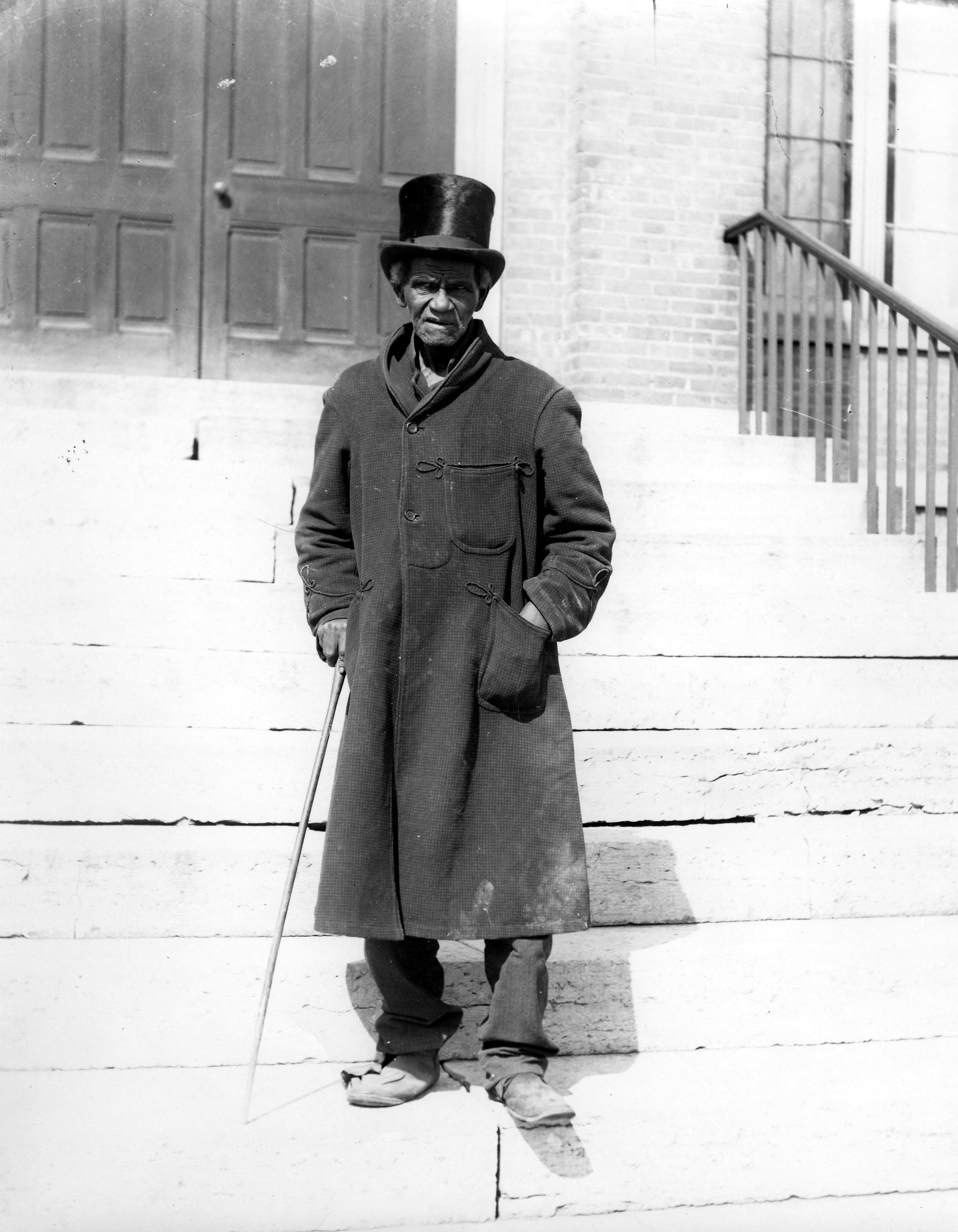

[Note: Throughout our post, we will be using terminology that was used at the time the records were created.] A ‘free negro’ or ‘free black’ was a fairly recent status in the U.S. which differentiated between an African-American person who was free and those who were enslaved prior to emancipation. If a person was referred to as a ‘free negro’ or ‘free black’, that meant the person was not living in slavery. It is a fascinating and little know fact that, as Ancestry Wiki states, “one in ten African-Americans was already free when the first shots were fired on Fort Sumter.”Step 1 for Tracing Free People of Color: Censuses

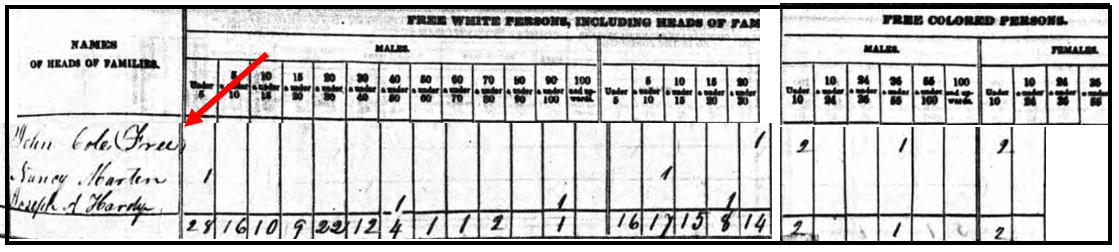

Sometimes, the story of your ancestors being free people of color was passed on through oral traditions. In my own family, our “line of color” was not talked about. Instead, my first clue was when I found my ancestor in the 1840 population census listed as free. I also found that one woman (presumably his wife) was marked in the column for “free white persons,” but John and the children were marked as “free colored persons” in this census. This was the first step to identifying my ancestor as a free person of color.

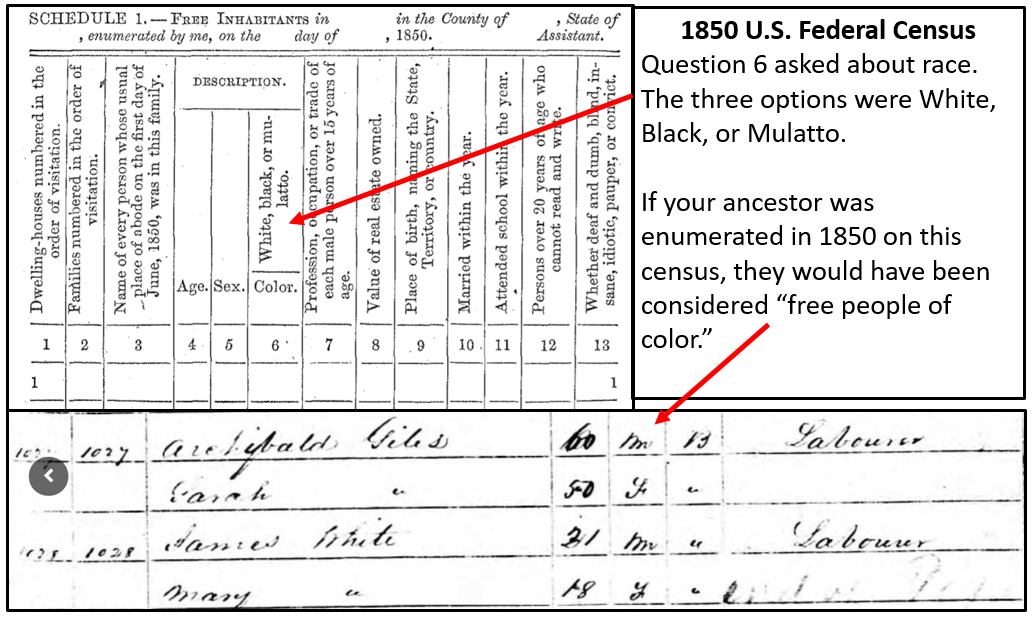

Let’s see another example. The 1850 and 1860 U.S. Federal Censuses included two population schedules. One enumerated free inhabitants, and the additional schedule, referred to as a Slave Schedule, was for making an enumeration of those persons who were enslaved. [We will discuss this further, below.]

If your ancestor appears on the 1850 U.S. Federal Census for free inhabitants, they are considered free, even if their race was listed as “Black.” An example of a Black man enumerated on the 1850 census is shown in the image below. Archibald Giles is recorded as “Black,” but appears on this census for “free inhabitants.” Therefore, he would be considered a free person of color.

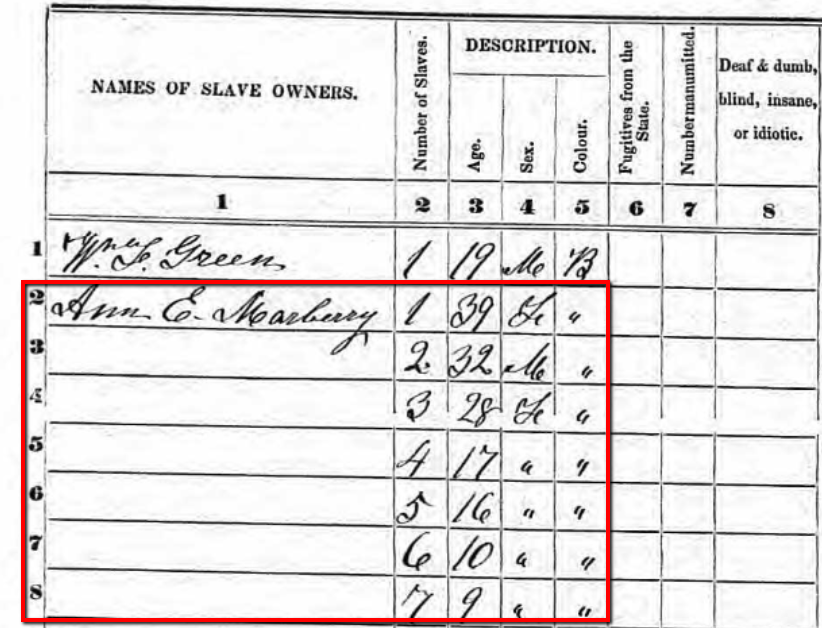

If your targeted ancestor does not appear on either the 1850 or 1860 population schedule for free inhabitants, they might have been enumerated on the slave schedules of 1850 or 1860.

1850 Slave Schedule for Henry County, Tennessee. Snapshot via Ancestry.com.

You can check the 1850 Slave Schedule and the 1860 Slave Schedules at Ancestry.com. The 1850 census is also available at Findmypast, MyHeritage, and FamilySearch.

In this example to the left, you will see a portion of the Henry County, Tennessee Slave Schedule for 1850. Notice, only the heads of household or the “owners” were listed by name. Slaves were not named, but rather listed by age and sex under the names of their “owners.”

Step 2: The Manumission Process

Once you have identified that you have free people of color in your family tree, the next step is to determine how they became free. Many free people of color came from families that had been free for generations. This could have been due to a manumission of an ancestor or a relationship between an indentured white woman and a black slave. I make mention of this relationship between races because it is helpful to remember that the status (whether free or enslaved) of the child was based on the status of their mother. If the mother was free, then the child was free. If she was a slave, then the child was enslaved. [1]

Manumission was a formal way in which slaves were set free. There are many reasons why a slave owner may have released or freed his slaves. In some cases, slave owners would free their mistresses and children born to her. In one case, I found the following comment made by the slave owner, “I give my slaves their freedom, to which my conscience tells me they are justly entitled. It has a long time been a matter of the deepest regret to me…” And thirdly, it was possible for a slave to obtain their manumission through the act of “self-purchase.”

If the mother was free, then the child was free. If she was a slave, then the child was enslaved. [1]

Private manumission through probate. A private manumission decree could be made in a last will and testament. You can find these manumissions in wills, estate papers, or in probate packets. Many of these county level probate records have been microfilmed or digitized and are easily accessible online.

Sometimes, a manumission in a will would be contested. When this happened, a long paper trail of court documents may have been created. A thorough search of all of these proceedings may offer a wealth of genealogical data and clues.

Usually, manumission papers included the name of the slave owner, the name of the slave, and the reason for manumission. In the case of the slaves of John Randolph of Roanoke [Virginia,] his slaves were not named individually in his will written on 4 May 1819. Instead he stated, “I give my slaves their freedom, to which my conscience tells me they are justly entitled. It has a long time been a matter of the deepest regret to me, that the circumstances under which I inherited them, and the obstacles thrown in the way by the laws of the land, have prevented my manumitting them in my lifetime, which is my full intention to do, in case I can accomplish it.”[2]

John freed over five hundred slaves, and though each of them was not listed by name in his will, a codicil at the end of the will did name two of his slaves when he asked that Essex and his wife Hetty “be made quite comfortable.”[3]

Manumission through self purchase. Self-purchase may seem impossible; however, many slaves were not required to work on Sundays for their masters.[4] On this day, men and women could hire themselves out to do work for others. With frugality, they could save their earnings to buy their freedom or the freedom of their loved ones, though this was very, very difficult.

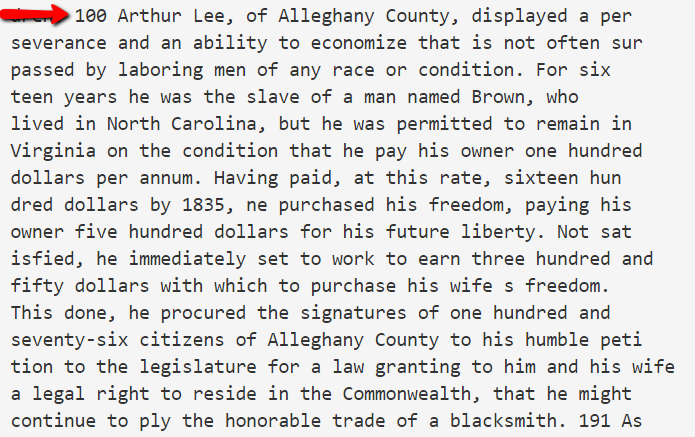

As you can see in this example of Arthur Lee, he was able to pay for his freedom and the freedom of his wife, though it took many years. This type of record could be found in a published book, a record listed in notarial books of the county, civil minutes books, or other courthouse holdings. It is important to speak with a knowledgeable person in your targeted area about where you should look. A knowledgeable person may be those working with the local historical or genealogical society, or a head of the local history department of the public library.

Step 3: “Negro Registers”

If you do not find the manumission in a last will and testament, perhaps due to a courthouse fire or other loss, you may have luck searching the county records where your free people of color later settled. Free people of color were often required to register, using their freedom papers, when they relocated to a new area. These types of records are called ‘negro registers’ or ‘records of free negros.’

Newly freed people carried with them their freedom papers which were given to them when they were manumitted. Once they relocated, they would register with the county clerk. They would need to show the county clerk these freedom papers and a record was made in the register. The record may include the name of members of the family, ages, and most recent place of residence.

The book titled Registers of Blacks in the Miami Valley: A Name Abstract, 1804-1857 by Stephen Haller and Robert Smith, Jr. provides the following information about registers of freed people:

“From 1804 to 1857, black people in Ohio had to register their freedom papers with the clerk of courts of common pleas in the county where they desired residency or employment. State law required this registration, and clerks of court were to keep register books containing a transcript of each freedom certificate or other written proof of freedom (see Laws of Ohio 1804, page 63-66; 1833, page 22; 1857, page 186). Few of these registers have survived to the 20th century.”[2]

Though this author says that only a few of the registers have survived, I found some microfilmed registers listing the names of free people of color who had settled in Miami County, Ohio at the local historical society archives. Again, it is important to ask those people who would be most knowledgeable, and in this case, it was the historical society.

In conclusion, we understand that tracing both our enslaved and manumitted ancestors is often a difficult task. We also know there is much more to learn and share for the best techniques to researching these lines. We encourage you to review some of the additional sources below. Please let us know what other resources have been most helpful to you in researching your free people of color in the comments section below. We want to hear from you!

Source Citations

[1] Kenyatta D. Berry, “Researching Free People of Color,” article online, PBS, Genealogy Roadshow, accessed 1 Dec 2016. [2] Lemuel Sawyer, A Biography of John Randolph with a Selection From His Speeches, New York: 1844, page 108, online book, Google Books, accessed 20 Dec 2015. [3] Ibid. [4] History Detectives Season 8, Episode 10, PBS, online video, originally aired 29 Aug 2010, accessed 1 Dec 2016.Additional Reading