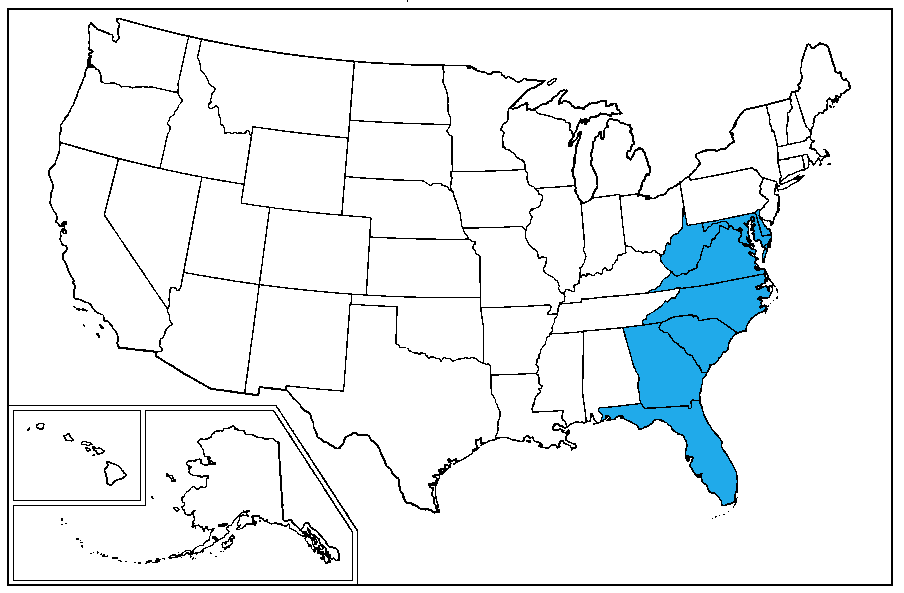

Mid-Atlantic and Southern Genealogy: Tips & Record Types

Researching your U.S. mid-Atlantic and Southern genealogy can be a challenge (ever heard of “burned counties?”). These top tips and key record types may help you bust your genealogy brick walls in these regions.

Thanks to Robert Call of Legacy Tree Genealogists for writing this guest post! Learn more about Legacy Tree Genealogists below.

The Challenge

Some of the most difficult genealogical research problems filter down to us through the poor record keeping, burned depositories, and social customs of our ancestors who lived in the Mid-Atlantic and Southern United States. Notoriously challenging, many of the requests that we receive at Legacy Tree Genealogists are to assist others in discovering their Southern ancestors. In this blog post, we’ll discuss some of the key record types we use when solving a Mid-Atlantic or Southern States problem.

Top tips for mid-Atlantic and Southern genealogy

First, three general tips are good to keep in mind when researching Mid-Atlantic and Southern ancestors.

1. Be patient

Research problems from these states generally require much patience—slowly chipping away at the problem at hand, searching out documents, considering the evidence, and letting it simmer. Rushing through a problem will result in missed evidence, conclusions with insufficient proof, or even just accidental errors. Giving a research problem time allows for more evidence gathering, more critical evaluation, and for fresh ideas and potential solutions to emerge from the documents and our analysis.

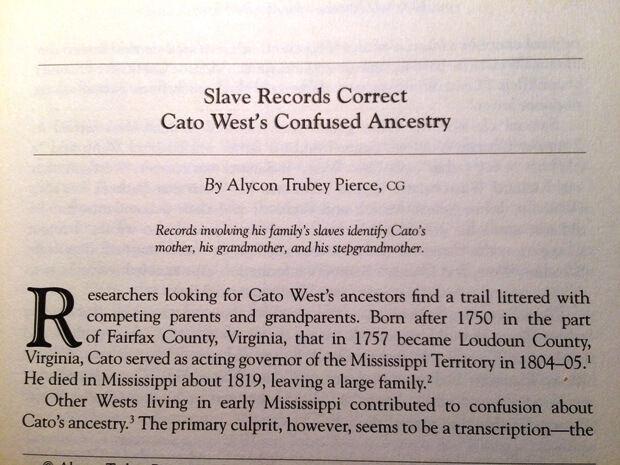

2. See what’s been done

Evaluate the pertinent work others have done on the same ancestral families. Usually, the best places to find the best research are periodicals such as National Genealogical Society Quarterly, The New England Historical and Genealogical Register (which publishes articles pertaining to all regions of the United States), and The American Genealogist. (The article shown here comes from the National Genealogical Society Quarterly Vol 99:1, March 2011, pp. 5-14.) In addition to these, there are state, regional, and local genealogy journals. [Note from Genealogy Gems: use PERSI, the Periodical Source Index at Genealogy Giant Findmypast.com to search for surnames and other subjects that appear in genealogy journal and newsletter articles. Click here to learn more about PERSI.]

Similarly, use search engines and library catalogs (such as the FamilySearch Catalog, university catalogs, and WorldCat) to discover whether book-length treatments of your family have been published. Because these volumes are usually not published by academic presses, are self-published, and are rarely peer-reviewed, the credibility of each history must be carefully evaluated but could offer important clues for your own research.

Online family trees at the Genealogy Giants, like the Public Member Trees at Ancestry.com or the global Family Tree at FamilySearch.org, may also provide good research or point to the holy-grail source—such as a property deed, family bible, probate document, etc.—that provides the necessary evidence. Of course, there is a lot of bad information floating around the Internet (including in online family trees) so be careful about what you accept as reliable. [Click here to watch a free video comparing the online tree model at Ancestry.com with the tree type used at FamilySearch.org.]

3. Befriend your ancestors’ friends

Pay attention to the extended kinship network and friends of your ancestors. These people often followed similar migration patterns, which can help you discover where ancestors originated, especially as people frequently moved throughout the South. For example, perhaps you know your Fitzpatrick ancestors in Georgia were born in North Carolina, but you cannot determine where in North Carolina. If many of the Georgian neighbors migrated from Rowan County, North Carolina, it would be worth a look in Rowan County’s records for your ancestors. Documents pertaining to aunts, uncles, cousins, or in-laws may shed light on your direct ancestors and help untangle the web of relationships that may not be clear from documents related to your ancestors.

Now for some insight into record types we frequently use for Mid-Atlantic and Southern States problems.

Top records for mid-Atlantic and Southern genealogy

Property records

This record type is one of the most useful when tackling families in the South or Mid-Atlantic regions. Property records document the transaction of real and personal property among the parties to the transaction. This usually means the transfer of land but could also include enslaved people or other high-value items (we’ve even seen the rights to use and sell a patent in designated areas recorded in property collections).

Property was often transferred among family members, which in turn helps the genealogist in his or her work. Family relationships are not always stated in deeds, but sometimes can be inferred from the phrasing. Even a possible relationship can be noted until additional evidence proving or disproving the hypothesis is discovered. And don’t ignore the witnesses! Property records usually include one, two, three or more witnesses attesting to the validity of the transaction and the witnesses were sometimes family.

Less-experienced genealogists sometimes only search the deed volumes, but a county may have kept other types of property records (mortgages being a common one) which should be searched as well. Property records are helpful when researching enslaved ancestors as well because they document the movements among various slaveholders and sometimes the enslaved person’s family relationships. Because property almost always constituted an inheritance—which fell to family members after debts were paid—the distribution of an estate is sometimes documented in the property collections rather than the probate records.

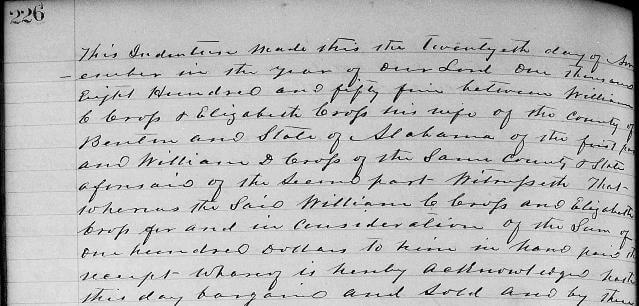

Excerpt from a property transaction between William C. Cross and his wife, Elizabeth, and William D. Cross, recorded in Calhoun County, Alabama. FamilySearch.org.

Probate Records

Probate records are the documents a court generates to distribute a deceased person’s estate. As mentioned above, the property almost always was divided among the deceased’s family members (instances where the testator chose to bequeath his or her property exclusively to non-family which was a rarity). Thus, in the absence of good vital records, as is the case in Southern and Mid-Atlantic states for most periods, probates may offer the necessary evidence to prove a family relationship.

A word of caution: That someone was listed as an heir to a deceased person’s estate is not proof that he or she was a child of the deceased. Frequently, when an heir was not a child, he or she was a grandchild of the deceased, suggesting the parent of the grandchild was deceased and his or her portion of the inheritance then went to the grandchildren. Like property records, probate records can also help in researching enslaved individuals because they were considered property in the law and were included in probate records as property sold to pay debts or bequeathed to the deceased’s heirs.

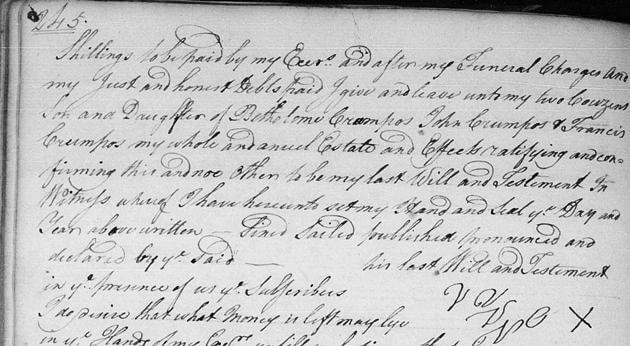

Excerpt from a 1730s will from Cecil County, Maryland, where the testator leaves property to his “couzens.” FamilySearch.org.

[Ready to learn more about probate records? Click here to read Gems contributor Margaret Linford’s reasons for loving these genealogically-rich records.]

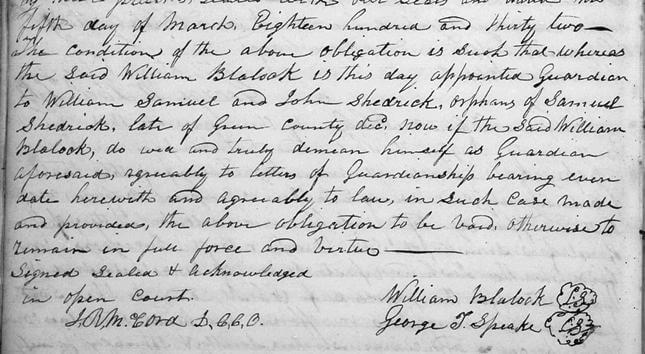

Guardianship Records

These records were created when a minor needed a legal guardian to represent them in legal matters (especially when the child inherited or could inherit property). It was not necessary for both parents to be deceased for a legal guardian to be appointed for a minor child. We have seen guardians appointed in instances when the mother was still alive, but the father deceased, and when the mother was deceased with the father still living. Guardianships can help prove a parent-child relationship or even whether a set of proposed siblings were truly siblings. These records also help prove the death of an ancestor. Guardians were sometimes older siblings, in-laws, grandparents, or extended families, so noting who the guardian was can help crack your Southern or Mid-Atlantic States research problem.

Excerpt from a guardianship bond from Butts County, Georgia appointing a guardian for William, Samuel, and John Shedrick, orphans of Samuel Shedrick. FamilySearch.org.

Civil court records

Once again, this type of record for mid-Atlantic and Southern states research problems often focused on property. When a dispute arose over property ownership, these matters were usually settled in the courts and there is a good chance that the documents pertaining to those proceedings may survive today. Disputes over property ownership may have been caused by conflicts regarding an inheritance. Or, perhaps neighbors argued over where a property boundary was located and the court records may document how the parties came about owning the property—which could have been through the family.

Court records may be more difficult to access because fewer have been microfilmed (the collections at the Family History Library in Salt Lake City, Utah, are a good place to start but are by no means complete) or digitized, so it may be necessary to contact the local courthouse or the state archives. But the patience and effort may be well worth the discoveries.

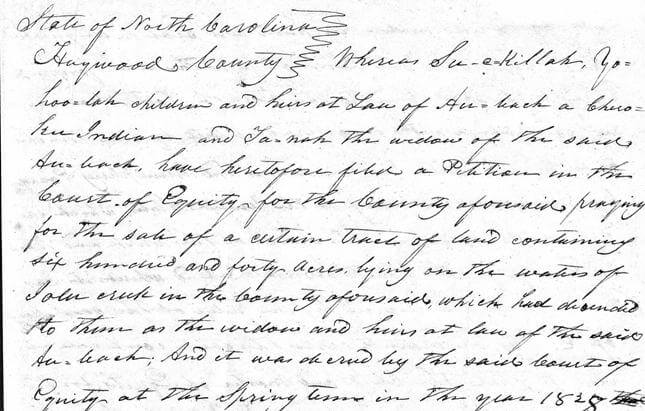

Excerpt from the 1820s civil actions collection of Macon County, North Carolina, naming Su-e-Killah and Yo-hoo-lah as the children and heirs of Au-back, a Cherokee Indian, and his widow, Ta-nah. Ancestry.com.

While Southern and mid-Atlantic States genealogy research is some of the most challenging research in the United States, solving those “brick wall” problems is exciting and satisfying! Patiently working through the property, probate, guardianship, and court records while searching for our direct ancestors and those connected to them can help extend our ancestries and discover previously unknown ancestors.

Robert Call is a researcher for Legacy Tree Genealogists, a worldwide genealogy research firm with extensive expertise in breaking through genealogy brick walls. To learn more about Legacy Tree services and its research team, visit www.legacytree.com. Exclusive Offer for Genealogy Gems readers: Receive $100 off a 20-hour research project using code GGP100! (Offer may expire without notice.)

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links and Genealogy Gems will be compensated if you make a purchase after clicking on these links (at no additional cost to you). Thank you for supporting Genealogy Gems!

A “house history” can tell you more about the house you live in–or your ancestor’s home. Here’s how.

A “house history” can tell you more about the house you live in–or your ancestor’s home. Here’s how.