Forensic Genealogy: Beyond the Golden State Killer Case

The Golden State killer DNA-credited arrest was just the beginning. Another cold case—a double murder—has new answers thanks to forensic genealogy research techniques and a company that helps criminal investigators use them. Though legal and privacy questions still remain, Your DNA Guide Diahan Southard points out a technology crime-fighters are refining that may prove beneficial to family historians.

Lisa recently shared with us in the Genealogy Gems Podcast episode 217 her thoughts on the ramifications of the Golden State Killer case, in which a murderer and rapist was arrested nearly 40 years after the crimes were committed, thanks to some excellent genetic genealogy work.

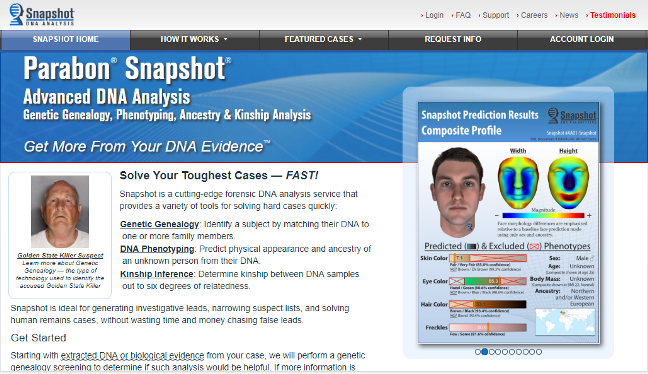

Just three weeks after that discovery made headlines, a police department in Snohomish, WA, announced that they too had employed genetic genealogy to solve a cold case from 1987, when two high-school sweethearts were found murdered. This police department indicated they had assistance from a company called Parabon Nanolabs, a genetics company based in Virginia.

According to their website, Parabon deals in both pharmaceuticals and something they call Snapshot, where they reconstruct the facial features of an individual based on their DNA. While they do have a press release on their website regarding the aforementioned case, they do not have a specific product on their website indicating they can take genetic material and make a DNA profile compatible with genetic genealogy databases (they do mention using “biological evidence” on the Forensics page, shown below). But that is exactly what they must have done in order to solve this case.

Forensic genealogy: Beyond the Golden State Killer

According to an article in The Star, a Toronto newspaper, the police department in Toronto has DNA on the perpetrators for 30 cold cases. It is very likely that every police department is harboring similar evidence. Up until now, either in the US or Canada, investigators have generally only matched DNA profiles from crime scenes to genetic databases of known criminals. These are people who have already been caught and convicted. If no match is found, investigators are back to square one.

In both the Washington state and Golden State Killer case, these men had never been caught, and therefore their DNA was not part of these national databases. The way the DNA evidence was made useful was to compare it with samples from the general population, or in this case, a bunch of genetic genealogists who had uploaded their DNA results to the open-source website, GEDmatch. (Click here to learn more about GEDmatch.)

In the podcast episode, Lisa discussed many of the ethical and moral issues that we need to address as more and more different kinds of uses for our DNA are found, employed, and even commercialized. These are conversations we need to have as a community, and certainly that you need to consider personally.

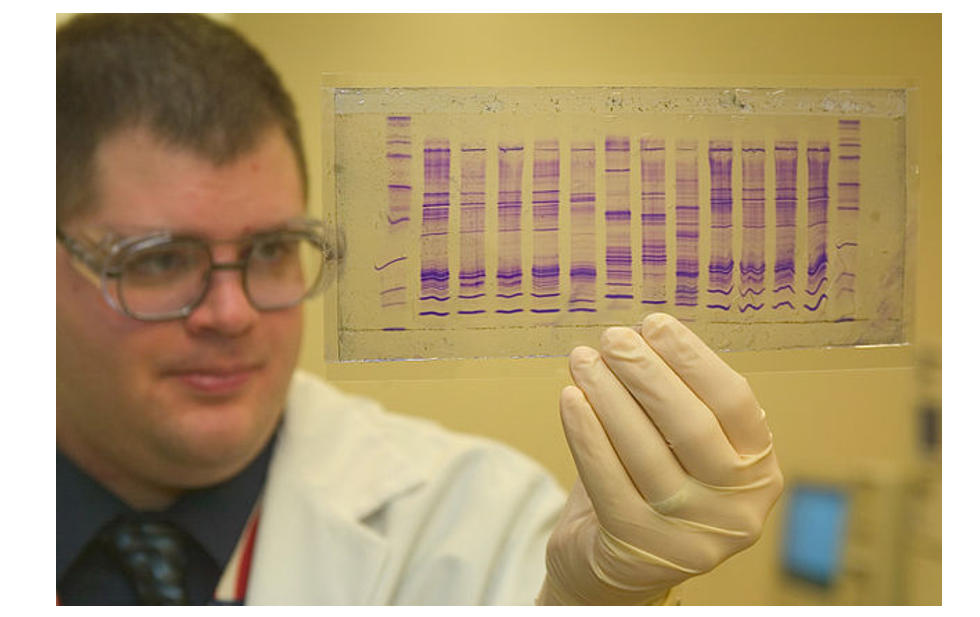

But like most technology, there are good sides and bad sides to advancements. One of the best upsides I can see out of this is the feat of technology that took a small amount of DNA found at a crime scene 40 years ago and turned it into a DNA profile that can be useful in genetic genealogy databases. For years I have disappointed many genetic genealogists that have letters and stamps and hats from their loved ones who have passed on, and they want a way to obtain their DNA. Well, now we have evidence that it can be done. You can take some genetic material (licked stamps or envelopes, hair with a root, razors, teeth), and use it to create a viable profile that can be used to search genetic genealogy databases!

In fact, LivingDNA is currently openly accepting these kinds of samples, albeit at a hefty price tag, starting at $1,000 or so per sample. (This service is new enough that they don’t even have a landing page for it yet; submit your inquiries through their contact form.)

Now, whether or not the DNA from that stamp, or that stray piece of hair in the hat will be able to produce enough DNA to provide a complete enough DNA profile, still remains to be seen. But I would watch closely companies like Parabon and LivingDNA as they work to develop robust laboratory techniques that will provide answers for all of the genealogists whose parents and grandparents didn’t ever have a chance to spit to record their family history.

About the Author: Diahan Southard has worked with the Sorenson Molecular Genealogy Foundation, and has been in the genetic genealogy industry since it has been an industry. She holds a degree in Microbiology and her creative side helps her break the science up into delicious bite-sized pieces for you. She’s the author of a full series of DNA guides for genealogists.

Keep up with what DNA can tell you

Stay at the cutting edge of what your DNA (or your relatives’ DNA) can tell you about your family history with Diahan’s Advanced DNA Bundle of quick reference guides, with try-it-now techniques for your DNA test results (click on individual titles to buy them separately or click here to save by bundling them together):

- Gedmatch: A Next Step for Your Autosomal DNA Test. GEDmatch is a third‐party tool for use by genetic genealogists seeking to advance their knowledge of their autosomal DNA test. This guide will navigate through the myriad of options and point out only the best tools for your genetic genealogy research.

- Breaking Down Brick Walls with DNA. With this guide in hand, genealogists will be prepared to take their DNA testing experience to the next level and make new discoveries about their ancestors and heritage. Learn how to leverage the power of known relatives who have tested, explore chromosome browsers, employ a methodology for finding a family tree for a DNA match that does not have a tree, and more.

- Organizing Your DNA Matches. With millions of people in possession of a DNA test, and most with match lists in the thousands, many are wondering how to keep track of all this data and apply it to their family history. This guide provides the foundation for managing DNA matches and correspondence, and for working with forms, spreadsheets, and 3rd party tools.