by Lisa Cooke | Dec 1, 2013 | 01 What's New, FamilySearch, Military, Records & databases

FamilySearch recently added another 192 million+ images and indexed records from North and South America and Europe to its growing FREE online collections. In the list at the bottom of this post you’ll find content from Brazil, Colombia, Peru, Spain, Switzerland, the United States, and Wales.

Notable collection updates include the 314,910 images from the Spain, Province of Barcelona, Municipal Records, 1387–1936,

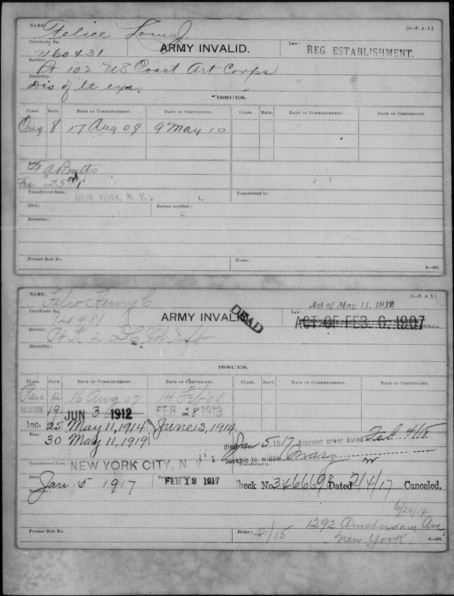

collection, the 576,176 indexed records from the United States Veterans Administration Pension Payment Cards, 1907–1933, collection, and the 189,395,454

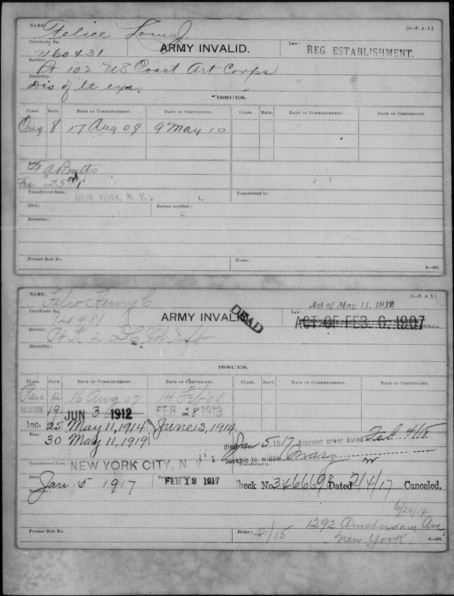

Sample image from “United States Veterans Administration Pension Payment Cards, 1907-1933.” Index and images. FamilySearch. https://familysearch.org : accessed 2013.

indexed records from the United States Public Records Index.

Here’s an example of a V.A. pension card, created by the Bureau of Pensions and Veterans Administration to record payments to veterans, widows and other dependents. FamilySearch describes the cards this way: “On the front of the cards for invalid veterans are recorded the name of veteran, his certificate number, his unit or arm of Service, the disability for which pensioned, the law or laws under which pensioned, the class of pension or certificate, the rate of pension, the effective date of pension, the date of the certificate, any fees paid, the name of the pension agency or group transferred from (if applicable), the date of death, the date the Bureau was notified, the former roll number, and ‘home.’ On the reverse side of the form appears the name of the veteran, his certificate number, and the record of the individual payments. The army and navy widow’s cards are similar to the invalids’ cards with the addition of the widow’s name and occasionally information regarding payments made to minors, but they do not indicate if the veteran had a disability.”

|

Collection

|

Indexed Records

|

Digital Images

|

Comments

|

| Brazil, Mato Grosso, Civil Registration, 1848-2013 |

0 |

126,870 |

Added images to an existing collection. |

| Brazil, Minas Gerais, Catholic Church Records, 1706-1999 |

0 |

827 |

Added images to an existing collection. |

| Brazil, Pernambuco, Civil Registration, 1804-2013 |

0 |

94,516 |

Added images to an existing collection. |

| Colombia, Catholic Church Records, 1600-2012 |

0 |

111,526 |

Added images to an existing collection. |

| Peru, Puno, Civil Registration, 1890-2005 |

0 |

176,918 |

Added images to an existing collection. |

| Spain, Province of Barcelona, Municipal Records, 1387-1936 |

0 |

314,910 |

Added images to an existing collection. |

| Switzerland, Fribourg, Census, 1839 |

0 |

2,552 |

New browsable image collection. |

| Switzerland, Fribourg, Census, 1842 |

0 |

2,851 |

New browsable image collection. |

| Switzerland, Fribourg, Census, 1845 |

0 |

3,062 |

New browsable image collection. |

| Switzerland, Fribourg, Census, 1850 |

0 |

2,968 |

New browsable image collection. |

| Switzerland, Fribourg, Census, 1860 |

0 |

20,530 |

New browsable image collection. |

| Switzerland, Fribourg, Census, 1870 |

0 |

22,554 |

New browsable image collection. |

| U.S., Alabama, County Marriages, 1809-1950 |

324,971 |

690,459 |

Added indexed records and images to an existing collection. |

| United States Public Records Index |

189,395,454 |

0 |

Added indexed records to an existing collection. |

| United States Veterans Administration Pension Payment Cards, 1907-1933 |

576,176 |

0 |

Added indexed records to an existing collection. |

| United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918 |

644,004 |

0 |

Added indexed records to an existing collection. |

| Wales, Court and Miscellaneous Records, 1542-1911 |

0 |

84,676 |

Added images to an existing collection. |

by Lisa Cooke | Nov 11, 2013 | 01 What's New, Collaborate, Dropbox, Family Tree Magazine, Inspiration, Research Skills, Technology

Recently Katharine, a Premium podcast member, asked for my advice on collaborating with a research partner. She wrote, “While I am primarily a digital  researcher, and have divested myself of duplicate papers, my research buddy uses a lot of binders and has many unconnected families in various computer genealogy programs. We need a good way to collect and focus our research.”

researcher, and have divested myself of duplicate papers, my research buddy uses a lot of binders and has many unconnected families in various computer genealogy programs. We need a good way to collect and focus our research.”

As it happens, Genealogy Gems Contributing Editor Sunny Morton and I just co-wrote an article on this topic. “Teaming Up” appears in the December 2013 issue of Family Tree Magazine. In honor of this article, we’ve prepared a companion series of blog posts on collaborating and are hosting a FREE giveaway for a digital subscription to Family Tree Magazine.

First, check out these strategies for deciding how to work with someone.

First, don’t judge or try to change each other too much. If one of you really wants to learn new tech tools or organizational methods, that’s great. But your strategy for staying organized and connected should be as easy as possible for both of you so you can focus on the research itself. Requiring an old-school genealogist to suddenly master Skype, Evernote and Dropbox to work together might be as unfair as asking a newbie researcher to locate unindexed court records and transcribe them in German!

Next, play to your strengths. Is one of you super organized, or a fast typist, or great at merging GEDCOMS or another skill that would move your project forward? Does only one of you have direct access to certain research materials (databases, manuscript sources, etc)? Talk about your individual strengths and interests and then divide the workload accordingly.

Mix it up. Often in any collaboration, one person is more tech-savvy than the other. Sometimes a combination of traditional and up-to-the-minute technologies will work best. For example, maybe you’ll decide to keep your shared files in Dropbox but communicate by old-fashioned telephone instead of Skype. Maybe one of you will organize everything online (or at least on the computer) and then mail printouts to a non-computer-user for review.

Watch this blog for more on technology tools for collaborating, and check out our article (which has lots of great exclusive stuff!) in the December 2013 issue of Family Tree Magazine

Watch this blog for more on technology tools for collaborating, and check out our article (which has lots of great exclusive stuff!) in the December 2013 issue of Family Tree Magazine  , available by digital and print subscription.

, available by digital and print subscription.

Check out the other posts in this series:

Tips for Collaborative Genealogy: Dropbox for Genealogists

Tips for Collaborative Genealogy: Evernote for Genealogists

Tips for Collaborative Genealogy: Sharing Genealogy Files Online for Free

by Lisa Cooke | Nov 4, 2013 | 01 What's New, Newspaper

Does your local library, historical or genealogical society have a newspaper collection to share? Let the NEH help!

The National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) is accepting proposals from institutions hoping to participate in the the National Digital Newspaper Program (NDNP). This program creates “a national, digital resource of historically significant newspapers published between 1836 and 1922 in U.S. states and territories.” Guidelines for 2014 are now available and proposals must be submitted by January 15, 2014.

According to the press release, “Each award supports a 2-year project to digitally convert 100,000 newspaper pages from that state’s collections, primarily from microfilm negative. Titles may be printed in Danish, English, French, German, Hungarian, Italian, Norwegian, Portuguese, Spanish or Swedish. The program provides access to this resource through the Chronicling America web site hosted by the Library of Congress. The site currently includes more than 6.6 million newspaper pages in English, French, German, and Spanish, from more than 1100 titles digitized by institutions in 30 states.”

For more program information, please visit the NEH’s program page or this page for technical information from the Library of Congress. Click here to see what institutions have participated.

I can’t say enough good things about this and other initiatives to support more digitized newspapers online. My book How to Find Your Family History in Newspapers will provide you with more about using these awesome resources to flesh out your family’s story, a tried and true research process, and loads of resources. Check it out in paperback or pdf e-book!

by Lisa Cooke | Oct 22, 2013 | Ancestry, Beginner, Family History Podcast, FamilySearch, Records & databases, Research Skills

Tune in Tuesday: The Family History: Genealogy Made Easy Podcast

Tune in Tuesday: The Family History: Genealogy Made Easy Podcast

Published October 15, 2013

by Lisa Louise Cooke

[display_podcast]

Download the Show Notes for this Episode

Welcome to this step-by-step series for beginning genealogists—and more experienced ones who want to brush up or learn something new. I first ran this series in 2008. So many people have asked about it, I’m bringing it back in weekly segments.

Episode 3: Working Backward and the SSDI

In our first segment in this episode my guest is Miriam Robbins Midkiff, a well-known genealogy blogger and teacher. She shares her best research tips, what motivates her to delve into her family history and how that discovery has enriched her life.

Then in our second segment we answer the question, “Why do we work backwards in genealogy?” and then fire up the Internet and go after your first genealogical record. Below, find current links to the record sources I talk about in the show. Also, when I recently checked, the Social Security Death Index was no longer free at WorldVitalRecords as I mention in the podcast and some of the site features I mention may have changed. I’ve given you links below to more options for searching, including plenty of FREE options!

Working Backward

When it comes to tracing your family history, there are standard methods that will help you build a solid family tree. Starting with yourself and working backwards is a cornerstone of genealogical research. It will be tempting to start with a great grandparent that you just got some juicy information on after interviewing Aunt Martha, but resist the temptation to start with that great grandparent, and go back to the beginning – and that’s YOU!

There’s a very good reason why working backward is so effective. Let’s say you have filled in info on yourself, and then recorded everything about your parents and now it’s time to work on one of your grandfathers and all you have is the date he died and the date he was born. If you are lucky enough to have his birth date and birthplace and you get his birth certificate it will tell you who his parents were, but it can’t predict his future can it? Where he went to school, where he lived over the years, etc. Documents can only tell you what has occurred in the past, not what will occur in that person’s future.

But if you get his death certificate it will give you key information at the end of his life that can lead you to the various events throughout his life. If you don’t have his birthdate and birthplace, you’ll probably find it on the death certificate. It will also likely name his parents and his spouse. A birth record can’t tell you who he will marry, but a death record can tell you who he did marry. You can start to see how starting at the end of someone’s life and working backwards will be the most efficient and accurate way to research.

Records are like the bread crumb trail of your family tree! If you don’t work systematically backwards, it will be very easy to miss a crucial piece of evidence, and you might end up relying on guesswork and end up building a false history on it. Believe me you don’t want to invest time in a tree that you’re going to have to chop down and replant!

So now that you understand and are committed to following this cornerstone concept of systematically starting with yourself and working backwards, it’s time to fire up the Internet and put it into practice by finding your first record. What type of record will we be looking for? A death record of course!

Is one of your parents deceased? If so, you’re going to start with them. If they are still living, and you’ve got their information entered into your genealogy database choose one of their parents, your grandparents, who is deceased – or if you’re lucky enough to be starting at a young age you may have to go back to a deceased great grandparent! (And good for you for starting now while you’re young!)

The SSDI

Chances are the person that you’ve chosen, for this example let’s say it’s your grandfather, he most likely had a social security card. And there is a wonderful free database online in the United States called the Social Security Death Index, what is commonly referred to as the SSDI, that you can use to find that grandparent.

In 1935 the Social Security Act was signed into law by President Franklin Roosevelt, and consequently more than thirty million Americans were registered by 1937. Today, the Death Master File from the Social Security Administration contains over 89 million records of deaths that have been reported to the Social Security Administration and they are publicly available online.

Most of the information included in the index dates from 1962, although some data is from as early as 1937. This is because the Social Security Administration began to use a computer database for processing requests for benefits in 1962. Many of the earlier records back to 1937 have not been added.

The SSDI does not have a death record for everyone; and occasionally you may find an error here and there if something was reported inaccurately, but overall it’s a terrific resource! As with all records it provides clues that you should try to verify through an additional record source.

There are many websites that feature this database, as seen in the UPDATED links below. This database is free at most sites, even sites that charge for access to other data.

On the Search page, enter your grandparent’s given name which is their first name, the family name which is their last name or surname, the place of their death – this could just be the state – and the year they died, and click the Search button. Hopefully you will get back a result that includes your grandparent.

Now remember you’re looking at an index, not an original record or primary source. We talked about sources in Episode 2. A primary source is a document that was created at the time of the event by an authoritative source, usually someone with direct personal knowledge of the event that’s being documented, like a death certificate is completed at the time of death by the attending physician. These are the best and usually most accurate types of sources you can find. And that’s what we want!

The really key information in this search result is the county information. In order to get an original death certificate which would be your primary source you have to know which county they died in. You may already know that for your grandparent, but keep this in mind because the further back we go, the more crucial it will be to know the county involved since that’s where death certificates are recorded.

By any chance did your grandparent not show up in the results even though you know they worked after 1937 when the Social Security got rolling, and you know they have passed away? Don’t fret – We have other ways to try and find the info!

This brings us to what I think is a really important concept to keep in mind whenever you’re researching your family on the Internet. Each search is conducted at a specific moment in time. Running an SSDI search or a Google search tomorrow might give you results different than the one you ran today. The Internet is being updated second by second, and the SSDI has been updated several times over the years.

In the case of the SSDI database, you can’t be absolutely sure that the website you are using to search the SSDI has the most current version available. Look in the database description on the site to see how recently it was updated.

Here’s a perfect example of that: When I searched for my grandfather on my dad’s side from the Family Tree Legends website, I got no results. Now I KNOW he died in 1971 and I KNOW he worked his entire life so he had to have been registered with Social Security. Then I went to Ancestry.com and searched for him in their SSDI database and he popped right up.

On the other hand, my maternal grandmother shows up on all three websites I’ve mentioned. In most cases, you’ll find who you’re looking for, but occasionally, like with my grandfather, you may have to dig in your heels and try the SSDI on a couple of different websites to find who them. Never give up, never surrender. That’s my motto!

And of course, each website offers just a little different variation on the terms that you can search on.

So just in case you have a stubborn ancestor who eludes your first SSDI search, try finding them at several of the SSDI databases. If you do have luck on World Vital Records, be sure and click the More Details link next to your search results because it includes some fun extras like a link called Historical Events next to their birth year and death year that will take you to a list of important historical events that were happening those particular years. It’s kind of fun to see what was going on in the world when your grandparent was born.

You’ll also find a link called Neighbors which will take you to a listing of folks who lived in the same county as your ancestor and died in within a year or two of them.

But most helpful is that your research results on World Vital Records will include a listing of nearby cemeteries which are good possibilities for where your ancestor may have been buried. (Again, just clues to hopefully send you in the right direction.) But as I said, the death certificate is going to be your best and primary source and almost always includes the name and address of the cemetery where the person was buried.

Here are a few more search tips if you don’t find your ancestor right away:

1. Make sure that you tried alternate spellings for their name. You never know how it might have been typed into the SSDI database.

2. Many SSDI indexes allow you to use wildcards in your search. So for example you could type in “Pat*” which would pull up any name that has the first three letters as PAT such as Patrick, Patricia, etc.

3. Try using less information in your search. Maybe one of the details you’ve been including is different in the SSDI database. For example it may ask for state and you enter California because that’s where grandpa died, when they were looking for Oklahoma because that’s where he first applied for his social security card. By leaving off the state you’ll get more results. Or leave off the birth year because even though you know it’s correct, it may have been recorded incorrectly in the SSDI and therefore it’s preventing your ancestor from appearing in the search results.

4. Leave out the middle name because middle names are not usually included in the database. However, if you don’t have luck with their given name, try searching the middle name as their given name. In the case of my grandfather his given name was Robert but he went by the initial J.B. But in the SSDI his name is spelled out as JAY BEE! Go figure!

5. Remember that married women will most likely be listed under their married surname, not their maiden name. But if you strike out with the married name, go ahead and give the maiden a try. She may have applied for her card when single, and never bothered to update the Administration’s records. Or if she was married more than once, check all her married names for the same reason.

6. Don’t include the zip code if there is a search field for it because zip codes did not appear in earlier records.

While most folks will appear in the SSDI, there are those who just won’t. But knowing where information is not located can be as important down the road in your research as knowing where it IS located, so I recommend making a note in your database that you did search the SSDI with no result. This will save you from duplicating the effort down the road because you forgot that you looked there. I admit it, in the past I’ve managed to check out books I’ve already looked through and order a record or two that I already had. Lesson learned!

So here’s your assignment for this week: Go through your genealogy database and do a Social Security Death Index search on every deceased person who was living after 1937. Hopefully you will be able to fill in several more blanks in your genealogy database and family tree!

Up next: Episode 4: Genealogy Conferences and Vital Records

by Lisa Cooke | Oct 22, 2013 | 01 What's New, Beginner, Conferences, Family History Podcast, Research Skills, Who Do You Think You Are?

Published October 29, 2013

Published October 29, 2013

[display_podcast]

Download the Show Notes for this Episode

by Lisa Louise Cooke

Welcome to this step-by-step series for beginning genealogists—and more experienced ones who want to brush up or learn something new. I first ran this series in 2008. So many people have asked about it, I’m bringing it back in weekly segments.

Episode 4: Attending Genealogy Conferences and Vital Records Requests

In our first segment, our guest is the longtime online news anchorman of genealogy, Dick Eastman, the author of Eastman’s Online Genealogy Newsletter. He talks about the changing industry and the benefits of attending genealogy conferences.

Next, you’ll learn the ins and outs of using some “vital” sources for U.S. birth and death information: delayed birth records, Social Security applications (SS-5s) and death certificates.

Genealogy Conferences Conversation: A Few Updates

- Dick and I talk about Footnote.com as a relatively small site. Has that ever changed! Footnote.com is now Fold3.com and it’s a go-to site for millions of online American military records.

- Family History Expos still offers an exciting conference, especially for first-timers. But there are others as well: In the United States, there’s RootsTech, the National Genealogical Society and many state and regional conferences (like one near my home, the Southern California Genealogical Society’s annual Jamboree). Find a nice directory at Cyndi’s List. Many conferences are starting to offer live streaming sessions for people who can’t attend: check websites for details. In addition, Family Tree University offers regular virtual conferences—where sessions and chat are all online! If you live outside the U.S., look for conferences through your own national or regional genealogical societies. If you can get to London, don’t miss Who Do You Think You Are Live.

- Dick now writes all of his Plus content himself. If you haven’t already checked out Eastman’s Online Genealogy Newsletter, you should! Both his free and Plus newsletters are great insider sources on what’s new and great (or not-so-great) in the family history world.

The SS-5

You can order a copy of the application that your ancestor filled out when they applied for a Social Security Number: the SS-5. I have done this, and they really are neat, but they aren’t cheap. So let’s talk about the facts you’re going to find on them so you can determine if it is worth the expense.

The SS-5 has changed slightly over time, but may include the applicant’s name, full address, birth date and place and BOTH parents’ names (the mother’s maiden name is requested). If your ancestor applied prior to 1947 then you will also very likely find the name and address of the company they worked for listed, and possibly even their position title.

Here’s an example of a Social Security application form:

In the 1970s, the Social Security Administration microfilmed all SS-5 application forms, created a computer database of selected information from the forms, and destroyed the originals. So it’s important to order a copy of the microfilmed original, rather than a printout or abstract from the Administration’s database. And luckily now you can request a Social Security Application SS5 Form online under the Freedom of Information Act.

It will help to have your relative’s Social Security Number (SSN) when you apply for a copy of their SS-5. First, it gives you greater confidence that their SS-5 exists. Second, it’s cheaper to order the SS-5 when you have their SSN. Third, the Social Security Death Index, in which you’ll find their SSN, usually has death data that makes your application for their SS-5 stronger. Privacy concerns have caused some genealogy websites to pull the SSDI, but you can still search it (in many instances for free) at the links provided in Episode 3.

Finally, here’s a little background on the Social Security Number itself. The nine-digit SSN is made up of three parts:

The first set of three digits is called the Area Number. This number was assigned geographically. Generally, numbers were assigned beginning in the Northeast and moving westward. So people whose cards were issued in the East Coast states have the lowest numbers and those on the West Coast have the highest numbers.

Prior to 1972, cards were issued in local Social Security offices around the country and the Area Number represented the state in which the card was issued. This wasn’t necessarily the state where the applicant lived, since you could apply for a card at any Social Security office.

Since 1972, when the SSA began assigning social security numbers and issuing cards centrally from Baltimore, Maryland, the area number assigned has been based on the ZIP code of the mailing address provided on the application for the card. And of course, the applicant’s mailing address doesn’t have to be the same as their place of residence. But in general the area number does give you a good lead as where to look for an ancestor.

The next two digits in the number are called the Group Number, and were used to track fraudulent numbers.

The last set of four digits is the Serial Number, and these were randomly assigned.

UPDATE: The website for ordering Social Security applications (SS-5s) has changed since the podcast first aired. For current ordering instructions, including online ordering, click here. The cost is still $27 to order a deceased relative’s SS-5 if you know the Social Security number and $29 if you don’t know it.

Delayed Birth Certificates

After 1937 folks who qualified to apply for social security had to have proof of their age. If they were born prior to official birth certificates being kept in their state, they applied for a delayed birth certificate.

Anytime someone needs a birth certificate for any reason, they have to contact the state—and often the county—in which the birth occurred. If a birth certificate exists, they can simply purchase a certified copy. But if there were no birth certificates issued at the time of the person’s birth, they could have a “delayed birth certificate” issued by that state or county.

In order to obtain a delayed certificate, they had to provide several pieces of evidence of their age. If these are considered satisfactory, the government would issue the certificate and it would be accepted as legal proof of birth by all U.S. government agencies.

Originally people turned to the census for proof of age. But eventually the Social Security Administration began to ask for birth certificates. For folks like my great grandmother who was born at a time and place where birth certificates were not issued, that meant they had to locate documents that could prove their age and allow them to obtain a delayed birth certificate. Delayed just meaning it was issued after the time of the birth.

Delayed birth certificates are not primary sources. (Remember we talked about Primary Sources in Episode 2. Since the delayed certificate was based on other documents, and not issued at the time of the event by an authority, such as the attending physician, then it is not a primary source. This means that while it’s great background information, it is more prone to error. In order to do the most accurate genealogical research you would want to try to find a primary source if possible. Chances are your ancestor used another primary source, such as an entry in the family bible, to obtain the delayed birth certificate.

The process for ordering a delayed birth certificate is likely going to be the same as ordering a regular birth certificate. You would start with the checking with the county courthouse, and then the Department of health for the state you’re looking in. Let them know that the birth record is a delayed birth certificate. Also the Family History Library card catalogue would be a place to look as many were microfilmed. Go to www.familysearch.org and search for delayed birth records by clicking on Search from the home page. Then click Catalog and do the keyword search just as the episode instructs, using “delayed birth” as your keyword. (Within that search, you can also add parameters for the place name.)

So the lesson here is that even though your ancestor may have been born at a time or in a location where births were not officially recorded by the state, they may very well have a delayed birth certificate on file.

Ordering Death Certificates

The Social Security Death Index is just one resource for getting death information. But in the end you’re going to want the primary source for your ancestor’s death, and that’s the death certificate. While many of your ancestor’s born in the 1800s may not have a birth certificate, there is a much better chance that they have a death certificate since they may have died in the 20th century. Each state in the U.S. began mandating death certificates at a different time, so you have to find out the laws in the state, and probably the county, since death certificates were filed at the county level.

As I said before, the death certificate is going to be able to provide you with a wealth of information. Of course you’ll find the name, date of death and place of death, and possibly their age at death and the cause and exact time of death, place of burial, funeral home, name of physician or medical examiner and any witnesses who were present. The certificate is a primary source for this information.

You may also find information such as their date and place of birth, current residence, occupation, parent’s names and birthplaces, spouse’s name, and marriage status. But because this information is provided by someone other than the ancestor themselves it is really hearsay, and the certificate is considered a secondary source for that information.

And lastly you may find a name in the box that says Informant. This is the person who reported the death to officials. Informants are often spouses, children, and sometimes, depending on the person’s circumstances, just a friend or neighbor. But the informant is almost always someone that you want to investigate further because they obviously were close to your ancestor.

Once you think you know the location where your ancestor died, and the approximate if not exact death date, you’re ready to order a certificate. If the person died in the last 50 years you’ll probably have really good luck at the county courthouse Department of Vital Records. The older the record, the more likely it may have been shipped off by the county records department to the state Department of Health. Look for helpful links to death records at Cyndi’s List Death Records.

Here are some tips that will ensure that you don’t get bogged down in bureaucratic red tape:

- Get the appropriate request form – this is usually available online.

- Print neatly and clearly – if they can’t read it, they will send it back to be redone.

- Provide as much information as you have.

- Provide a self addressed stamped envelope.

- Make one request per envelope.

- Include a photocopy of your driver’s license to prove your identity.

- Be sure to include your check for the exact amount required.

- Make a copy of the request form for your records and follow up.

- Lastly, keep in mind that county offices have limited personnel and are often swamped with paper work. So my best advice is that the more courteous and thorough you are the more success you’ll have.

Online Death Indexes

In the case of very old death certificates, as well as birth certificates, some state agencies have opted to hand them over to state Archives and Historical Societies, or at least make them available for digitizing.

And there you have it, lots of different avenues for tracking down your ancestor’s death records providing you with key information for climbing your family tree.

Page 6 of 11« First«...45678...»Last »

researcher, and have divested myself of duplicate papers, my research buddy uses a lot of binders and has many unconnected families in various computer genealogy programs.

researcher, and have divested myself of duplicate papers, my research buddy uses a lot of binders and has many unconnected families in various computer genealogy programs.  Watch this blog for more on technology tools for

Watch this blog for more on technology tools for