Beginning German Genealogy: Defining “German”

Beginning German genealogy research starts with a key question: “What does ‘German’ really mean?” A Legacy Tree Genealogists expert responds with a story about ancestors whose German identity in the U.S. census seemed to keep changing—and why that was so.

Thanks to Camille Andrus of Legacy Tree Genealogists for providing this guest post.

What does “German” really mean?

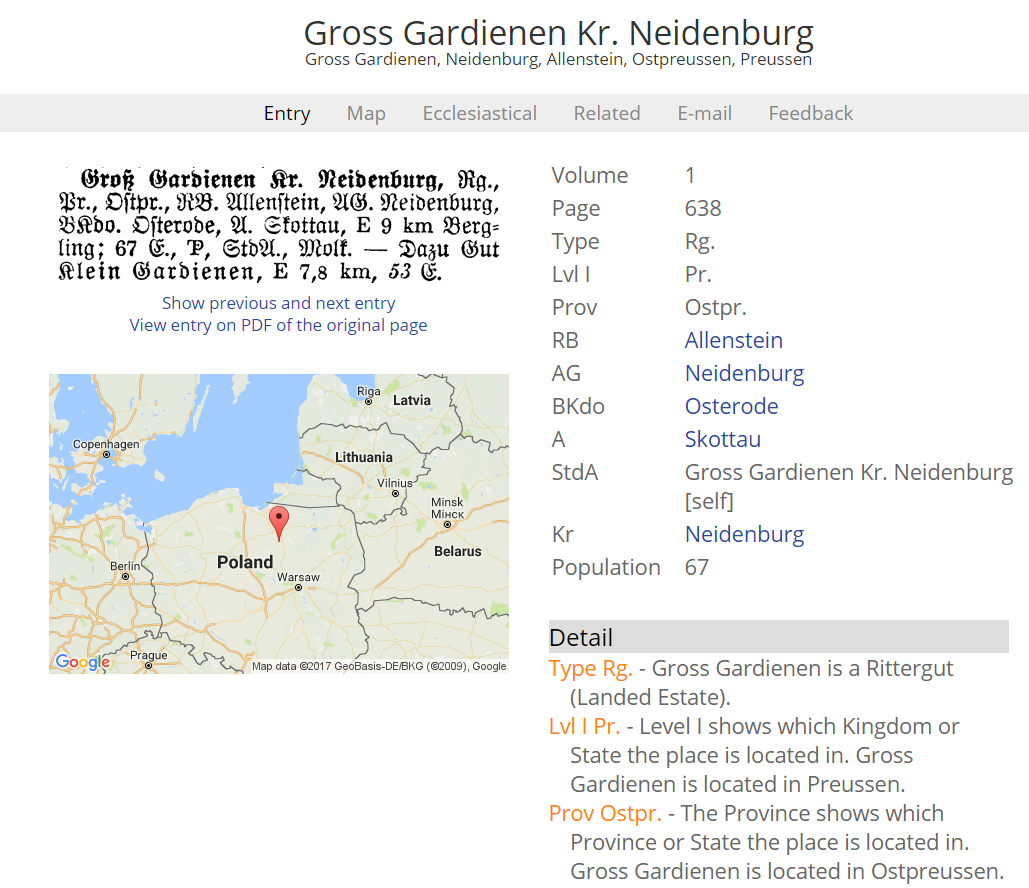

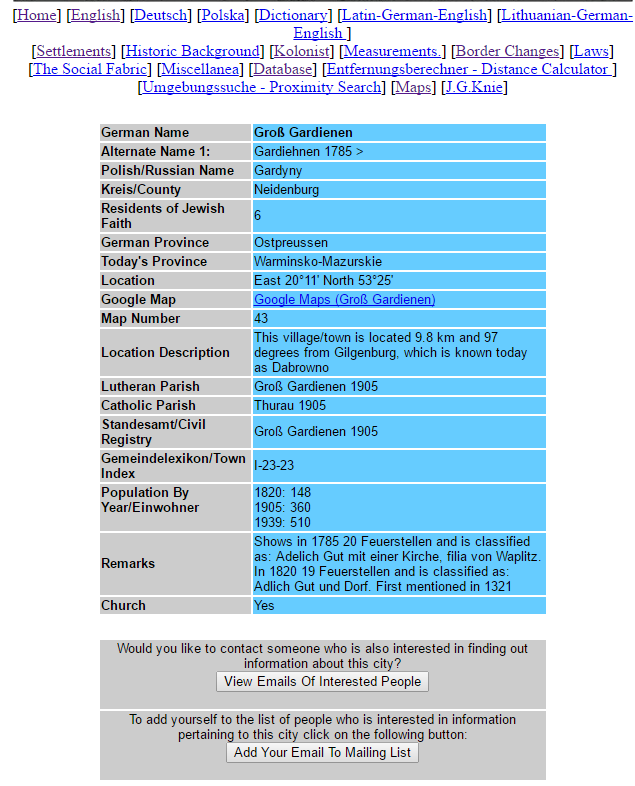

My great-grandmother Erika was German. She was adamant about the fact that she was German. After her arrival in the United States, when she was asked to fill out information about her place of birth, she indicated that she was born in Germany. Erika was born in 1921 in Waschulken. Today, this small town is located in northeastern Poland. However, at the time, it was part of Germany. Although borders have since been moved, she never stopped claiming she was German.

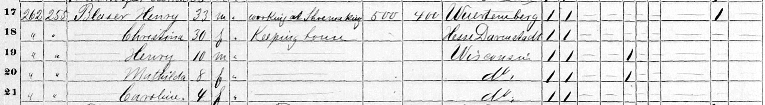

In the United States, many German immigrants were listed on various federal censuses and other documents generically as being from Germany. Instructions given to census takers for the 1870 census notes that the country of birth for individuals who were born outside the United States was to be listed “as specifically as possible.” In the case of those from Germany, census takers were to “specify the State, as Prussia, Baden, Bavaria, Wurtemburg, Hesse Darmstadt, [etc].” (Click here to read those instructions for yourself.) This makes sense, as the unification of Germany had not yet occurred.

Above: 1870 census for Henry Blaser household (Henry listed as from “Wuertemberg” and Christina listed as from “Hesse Darmstadt”). Click here to view on FamilySearch.org.

Instructions for the 1900 census, however, indicate that census takers should “not write Prussia or Saxony, but Germany.” Also, in the case of Poland, they were to “inquire whether the birthplace was what is now known as German Poland or Austrian Poland.” (Click to read.) Thus, at least in theory, earlier census enumerations should indicate a more specific area or region rather than the generic “Germany.” (In practice, some census takers still used “Germany” in lieu of a more specific place.

Above: 1900 census for Henry Blaeser household (husband and wife both listed as from “Germany”). Click here to view this entry on FamilySearch.org.

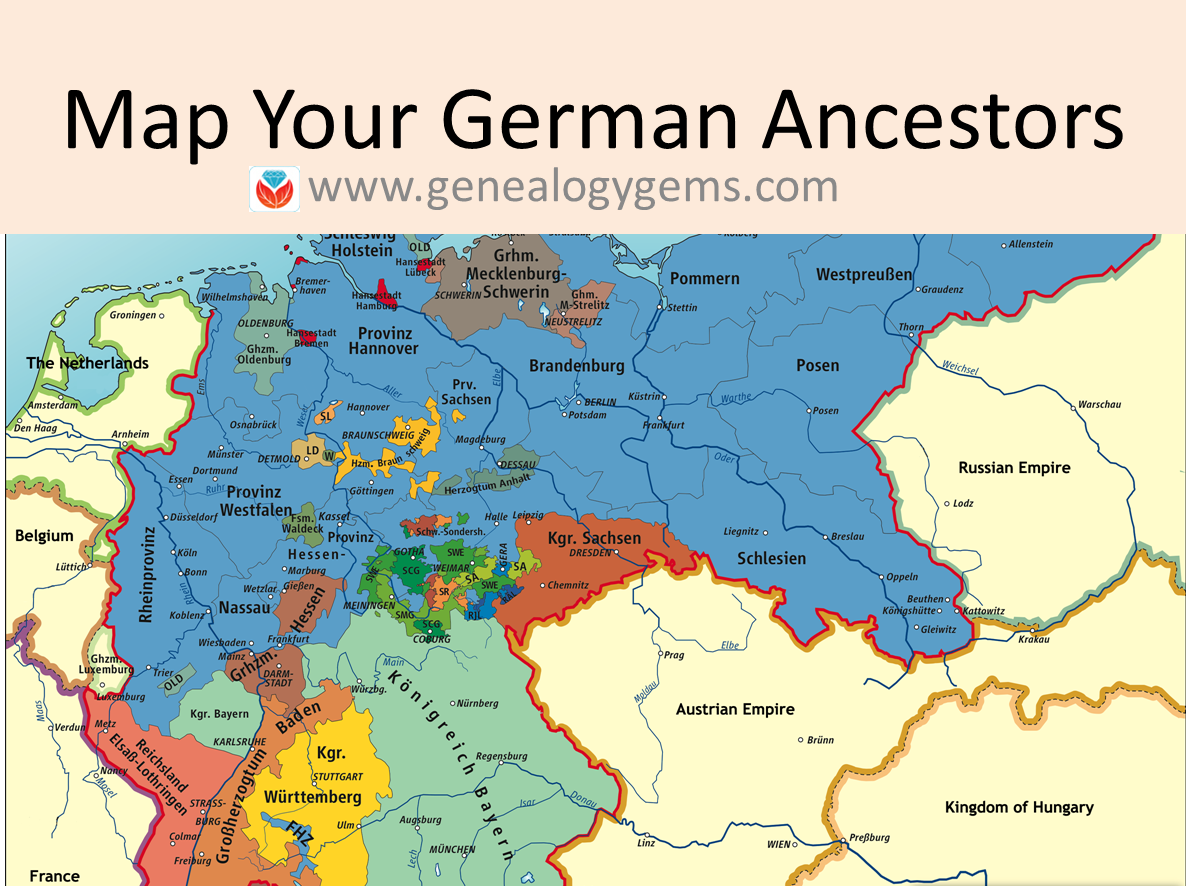

The unification of territories in January 1871 created the German Empire, which lasted until 1918. Prior to the merger, the area consisted of a multitude of separate kingdoms, duchies and provinces. When an individual claims to have German ancestry, they often mean that their ancestors lived within German Empire borders (although not necessarily only during the empire period). These borders were much larger than that of modern Germany, with the most striking inclusion being a large portion of northern Poland. Even after the fall of the empire in 1918, it took many years for the borders to shrink to their current position.

Beginning German genealogy research

Because the concept of who is “German” and what areas are considered “Germany” have changed frequently over time, it is vital to keep shifting historical boundaries in mind if you have ancestors who claim to be German. They may not be from the area of modern Germany.

However, even knowing the province your immigrant ancestor came from is usually not enough to begin researching in German record collections. You need to know the name of the town your ancestor came from. Although in some rare cases you may be able to identify your immigrant’s foreign hometown through indexes created from German collections, more often than not, traditional research will necessitate using church records, civil vital records, passenger lists, naturalization records, newspapers, and other such records in the country to which your ancestor immigrated in order to identify their place of origin.

Church records can be especially useful if the immigrant attended a church associated with their native language, as these records often list foreign hometowns in marriage and death entries. For German immigrants belonging to various Protestant faiths in the Midwest region of the United States, the book series German Immigrants in American Church Records is a quick source to see if your immigrant’s name appears in the extracted records. (Click here to see this book series in the FamilySearch Catalog. Look at the description for each volume, then click View this catalog record in WorldCat for other possible copy locations to look for the volume you need at a library near you.)

Newspaper articles including obituaries can also provide the name of the immigrant’s hometown. Where available, foreign language newspapers should not be overlooked as obituaries in such papers often provide additional details not listed in their English language counterparts. Check with local libraries or historical societies to see if they have copies of foreign language newspapers.

Although early passenger lists and naturalization records usually only list a province or “Germany” as an individual’s place of origin, naturalization records post-1906, as well as more modern passenger manifests, often do list exact towns of birth. On occasion, less-obvious records, such as wills, list the town of birth. So it is important to check all record types in search of the immigrant’s town of origin.

Once the town has been identified, church records and civil registration records, mandatory for the whole German Empire as of 1876, will be the most widely used sources for researching your German ancestors in Europe. (Click here to read about German census records, too.) As many of these records will be written in the antiquated German script, one will not only need to learn basic German genealogy vocabulary but also learn to recognize those words written in the old script. (Click here for a list of top German translation websites.)

Get help beginning your German genealogy

Camille Andrus is a Project Manager for Legacy Tree Genealogists, a worldwide genealogy research firm with extensive expertise in breaking through genealogy brick walls. She and their other German specialists are skilled not only in identifying German hometowns of immigrants, but also in reading and analyzing old German church and civil records. They would love to help you trace your German immigrant ancestors back to their hometowns and extend their lines there. To learn more about Legacy Tree services and its research team, visit www.legacytree.com. Exclusive Offer for Genealogy Gems readers: Receive $100 off a 20-hour research project using code GGP100.

Disclosure: This article contains offers with affiliate links, which may expire without notice. Genealogy Gems will be compensated if you make a purchase after clicking on these links (at no additional cost to you). Thank you for supporting Genealogy Gems!

Camille Andrus is a Project Manager for Legacy Tree Genealogists, a worldwide genealogy research firm with extensive expertise in breaking through genealogy brick walls. Her expertise includes Germany, Austria, German-speakers from Czech Republic and Switzerland and the Midwest region of the U.S., where many Germans settled.

Camille Andrus is a Project Manager for Legacy Tree Genealogists, a worldwide genealogy research firm with extensive expertise in breaking through genealogy brick walls. Her expertise includes Germany, Austria, German-speakers from Czech Republic and Switzerland and the Midwest region of the U.S., where many Germans settled.