How to Research Your Ancestors’ Occupations

Tracing your ancestors’ occupations can be one of the best ways to learn more about their everyday lives, skills, financial status and even their social status. Follow these tips and record types into the working lives of your relatives to enrich your family history.

One of my favorite things to learn about my ancestors is the kind of work they did. Whether they were laborers, owned a business, worked on a farm or clerked in a store, there are often records that can tell you more about what their working conditions would have been like; what skills they likely had; and what kind of perks (or lack of) came with the job, like wealth or social status.

Not long ago I heard from Deidre, who was thinking along the same lines. She’s already explored many records that can tell you about an ancestor’s occupation, and now she wants to take things a little further:

“Hi, Lisa! I have listened to most of your podcasts…and have come across something I need some help with. I don’t remember any episodes on business owners and how to research them. I have been recently been researching a new part of the family and they were business owners. One of these family members had a taxi business in Parkersburg, WV then moved to Indianapolis (where I live) to open a restaurant in our downtown, then owned an apartment/business building and leased it out. One of his sons owned drug stores and another was a lawyer.

By using city directories I have found some information about the business, but still wondering if I might be missing more record types. I have used censuses, city directories and local newspapers so far, but are there official legal documents filed for businesses and where would I look? And were there censuses conducted for businesses that would have some detail about the business? The time period I am referring to is 1900 to 1960’s.

It seems this family were entrepreneurial types and tried a lot of business ventures. I had also thought of going down the deed record way for looking at buildings they may have bought, but wondered if these are typically stored in the same place as land deed records at the courthouse. LOTS OF QUESTIONS TO KEEP ME UP AT NIGHT! Any insight is much appreciated! Thank you so much for your show!”

Deidre’s family sounds fascinating—no wonder she wants to learn more about their work! She’s already off to a great start, having learned what kind of work they did. If you need to start from square one, turn to the same kinds of records she already has.

How to research your ancestors’ occupations

1. Identify their line of work

A host of records created about your ancestors may reveal what kind of work they did and who employed them. Census records, obituaries, marriage or death records, city directory entries, draft registration records, pension records, local or county histories: all might mention an occupation.

A photo may reveal an occupation, too. Here’s one that does: see the H.R. Cooke’s Carriage and Motor Works sign in the upper left corner of this photo? It’s from my husband’s Cooke family.

So may a notation on a local map, which might identify an ancestor’s mill, store, school, a factory or hospital that employed him, etc. Remember, our ancestors’ jobs changed over time. A young man may have progressed from a laborer in a mine to the brake man on the coal train to a shift supervisor. Relatives may have changed career paths altogether, too.

When looking through these old records, watch for the name of an employer. The name of a business is just as researchable as an industry or type of work! (More tips on researching the business below.)

2. Learn more about the trade

Depending on the time period and the trade itself, you may be able to learn various details about what the work typically involved (even if you don’t learn specifics about your ancestor’s experience).

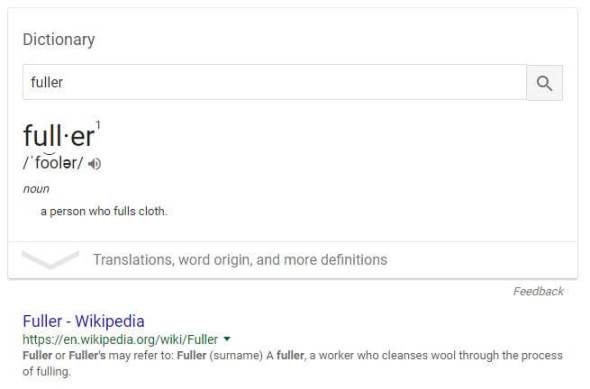

Many terms we see in old records today apply to jobs that no longer exist. Googling an obsolete occupation may help you identify it. For example, if you Google the question, “What is a fuller?” you’ll see a definition at the top and, below that, a clickable explanation at Wikipedia. (For the sake of accuracy, you’ll want to verify that in more scholarly sources.)

I saw once on Facebook that someone was trying to figure out what an occupation was that was on a 1910 census. It turned out to be “Topper” at a Stocking Mill. I guess they added the top band to socks or stockings! (Here’s a fun article done by the folks at MyHeritage.com: 10 jobs that no longer exist. And here’s a list of now-obsolete occupations taken from a U.S. census. If your ancestor’s UK census entry is abbreviated, click here to see what that notation might mean.)

These dictionaries of obsolete occupations may help, too:

You can learn more details about historical occupations in history books and documentaries, some of which you can find online. Use smart Google search methodologies to discover what resources are right at your fingertips.

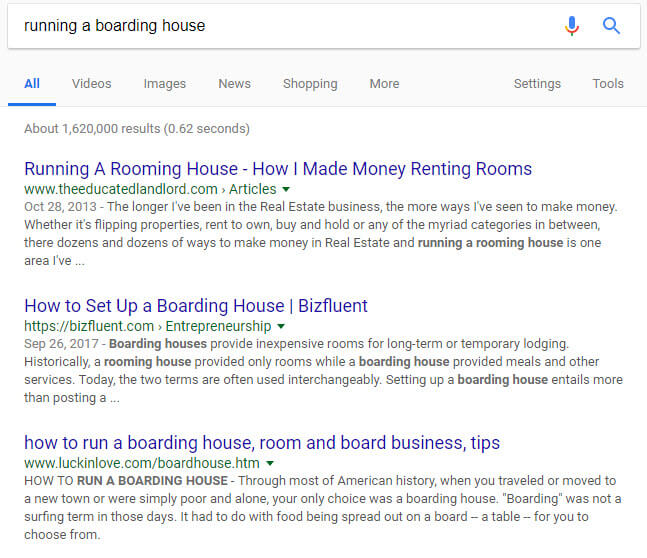

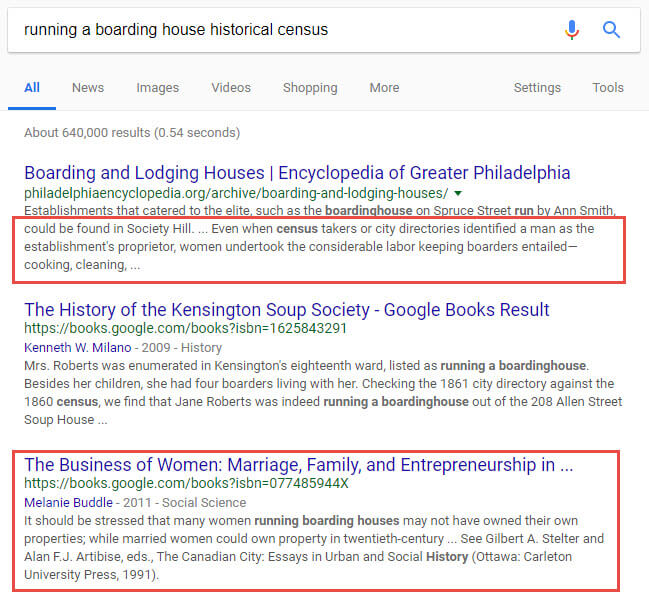

Here’s an example: Let’s say you discover from a census entry that your great-grandmother was running a boarding-house (or perhaps her husband was listed as the proprietor, but you are guessing she probably did a lot of the daily work for it). Googling the phrase running a boarding house gets you top search results about the modern practice of running a boarding house. Instead, add two more words to your search: historical and census (the latter will capture results about this occupation as it appears in the census). As you can see from this revised search, the top results are exactly the kind of thing you want to read.

Note that the second and third search results are from Google Books (the URL in the search result starts with “books.google”). The first appears to be a history book and the second an academic study. Books written by experts in their field and packed with citations are just the kinds of high-quality research sources you want to find. (Click here to learn more about using Google Books.)

Historical documentaries and old film footage can show you an occupation at work, such as mining, working on the railroad, logging, working at a textile mill, sharecrop-farming. Look for these on YouTube. For example, Contributing Editor Sunny Morton was curious after learning from a city directory that her grandmother was a telephone operator in the 1940s. What did that involve?

She went to YouTube and found some fantastic 1940s-era training videos showing operators at work. While some of these may be staged performances, with every operator smiling for the camera and doing her job in tip-top shape, they do show long rows of operators at their stations and give an idea of what their responsibilities were. Sunny could see how they were expected to dress and behave and what their daily tasks looked like. Here’s a quick example of the kinds of short training videos she found:

The idea that telephone operators handled emergency calls surprised Sunny, who grew up in the 9-1-1 era. As a young woman just past high school, Sunny’s grandmother would have been coached to respond to frantic callers and dispatch first responders. Sunny’s grandma would also have received training on how to handle different kinds of calls, such as party lines and long-distance routing through multiple switchboards.

Click here for tips on finding old film footage online. Just for inspiration and proof that this really does work, here’s a video Sunny found after following my tips: it’s her husband’s great-grandfather driving his fire engine in 1937! (Click here to read Sunny’s story about that amazing discovery.)

3: Look for any records created by or about the business itself

If your relative worked at a major factory or mill, such as The Ford Motor Company or Lowell Mill, you may find historical books, documentaries and even museum exhibits specifically about them. But smaller businesses often received a shout-out in local history books, too. So it can pay off to run Google searches with the names of family businesses (or even the type of business, such as tailor, hotel or restaurant) and the name of the town and state. (Add the word history to narrow search results.)

Here’s an example an ecstatic Genealogy Gems listener sent in. He was tipped off by an old map about a place called Todd Pond in his ancestor’s small town. His ancestors were surnamed Todd and lived right there. So he Googled Todds Pond North Attleboro and found a real gem! His family’s business was mentioned in a local history:

“In the days before electric refrigeration, North Attleborough’s homes and stores relied upon ice harvested from either Whiting’s Pond or Todd’s Pond (depicted here). By the time this 1906 photograph was taken, farmers George, Henry, James, and William Todd found selling ice more profitable than farming and founded the Oldham Ice Co.”

(For copyright reasons, we can’t show the picture here. But click here to read more about Thom’s discovery and access the book for yourself.)

Businesses themselves often created records. Stores kept ledgers. Factories and other businesses may have kept personnel records and employee pay cards. They may have published newsletters or histories. Sunny shared the following two fun examples with me:

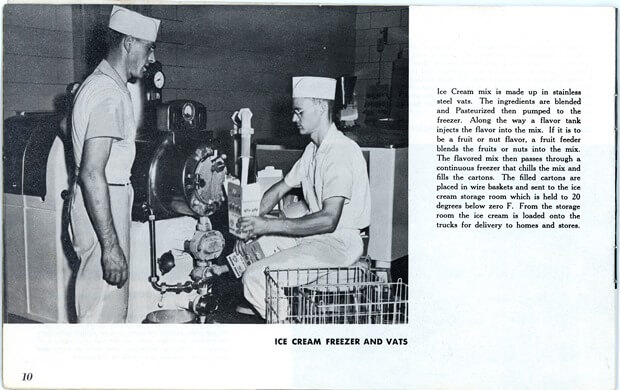

City directories from the 1950s state that her grandfather worked at the Sinton Dairy (he was the husband of the telephone operator, who by this time was a stay-at-home mom). Among the family papers handed down to one of their children was a company brochure. A picture in the brochure shows him standing next to a vat of ice cream.

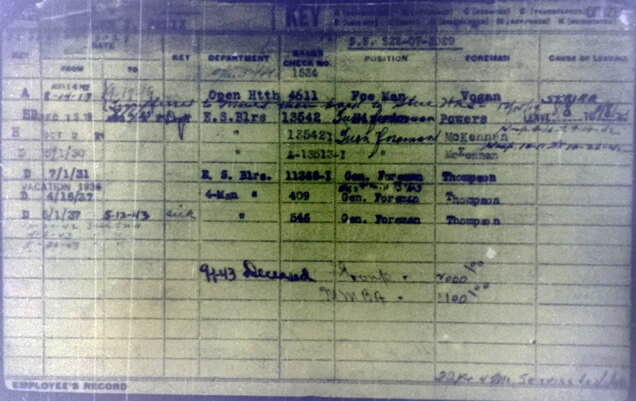

The father of the ice cream man, Sunny’s great-grandpa, worked at Colorado Fuel & Iron for most of his life. Her mom Cheryl, a professional genealogy librarian, visited the Steelworks Center of the West, which holds the records of the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company in its archive. Cheryl was able to get a copy of her grandfather’s employment application and work record. Though it’s partly illegible, this work record summarizes his dates of employment and steady progress through the ranks to become a foreman.

It’s possible you’ll find museum or archival collections like the one mentioned above by doing Google searches on the name of the company, place and industry. But you may need to search more specifically in ArchiveGrid, which is an enormous catalog of the original manuscript holdings of thousands of archives, libraries, museums and societies. Click here to learn more about using ArchiveGrid.

Now back to Deidre’s question

Deidre’s email shows she was thinking outside the box already about records that might document her family’s business, such as deeds for business properties. In addition to the above strategies, Deidre may next want to start hunting for the following:

- Local histories that may mention her family’s businesses

- Original archival records pertaining to the businesses

- Maps showing her family’s neighborhood at the time, specifically Sanborn maps, which often identified businesses and included some detailed information about properties.

Deidre specifically asked about legal documents or censuses conducted for businesses for the period 1900-1960s. The special U.S. census schedules relating to specific businesses and industries largely only exist with individual data before this time period. Legal documents would need to be researched on a case-by-case basis: it’s very possible at least one of those businesses faced lawsuits, bankruptcy or other issues that would have taken them into court. Click here to read up on researching on courthouses.

Another possibility is professional directories that could have been published specific to her relatives’ line of work. Here’s a link to an Ancestry.com wiki article on professional directories: the first category mentioned is law directories.

Finally, it might be helpful to contact the local genealogical and historical societies for the areas they lived. Often, a longtime local may know about gems that may only be on library shelves or tucked into a manuscript collection that isn’t listed in ArchiveGrid.

Learn more about ancestors’ occupations

Now that you’ve finished reading, I encourage you to go back and click on links provided to learn MORE about discovering ancestors’ occupations. If you’re ready to learn advanced online research skills (like mastering Google searching and Google Books) please consider becoming a Genealogy Gems Premium member. You’ll have access to full-length video tutorials on these topics and more–for a full year! To give you a taste of Premium, here’s a preview of my Google Books class.

About the Author: Lisa Louise Cooke

Lisa is the Producer and Host of the Genealogy Gems Podcast, an online genealogy audio show and app. She is the author of the books The Genealogist’s Google Toolbox, Mobile Genealogy, How to Find Your Family History in Newspapers, and the Google Earth for Genealogy video series, an international keynote speaker, and producer of the Family Tree Magazine Podcast.

He didn’t think much more of the next Head of Household 55 year old James Coleman who he labeled “Blow Hard.”

He didn’t think much more of the next Head of Household 55 year old James Coleman who he labeled “Blow Hard.”