Cemetery research is a crucial family history skill. Tombstones are monuments to our ancestors lives and may have key genealogical clues engraved in the stone. Follow these four steps to finding your ancestors’ burial places and the records that complement them.

Many of my ancestors are buried just two miles from my house in Round Hill Cemetery in Marion, Virginia. I drive by the cemetery each day, as I take my daughters to school. I never pass by without glancing up at the hallowed ground which holds the remains of those who came before me. The sun perfectly illuminates their resting place each morning and a majestic tree stands at the very top of the hill–a living monument to the lives they led in the town where I now raise my own family.

It is an emotional experience to stand in the place where an ancestor’s remains have been laid to rest.

Each time I visit the grave of my grandma, I have a vision of a family standing around a casket on a bitter cold day in March. It was a just few days before the official start of spring, but it was the dead of winter to me. That ground is sacred to me, now.

Each time I visit, I am transported back in time to that day. A wound is re-opened for a moment, but the moment is fleeting because I quickly remember her life, not her death.

I remember the stories she told, the service her hands rendered to her family and, most importantly, the love that transcends time and even the icy grip of death. Death truly loses its “sting” as we stand before a monument of stone and see beyond to the life it represents. Scenes like this one have played out at each grave.

I am reminded of this quote from Fear Nothing, a Dean Koontz book, whenever I visit the cemetery:

“The trunks of six giant oaks rise like columns supporting a ceiling formed by their interlocking crowns. In the quiet space below, is laid out an aisle similar to those in any library. The gravestones are like rows of books bearing the names of those whose names have been blotted from the pages of life; who have been forgotten elsewhere but are remembered here.”

I have often gone to my ancestors’ resting places to take pictures of headstones and search for relatives I may have missed in the past. It seems like each time I visit, I notice something new.

This library of marble holds many clues that have helped me break down brick walls in my family history research. These clues have been there, etched in stone, for decades. It wasn’t until I recognized how to read the clues that I began to understand the importance of cemeteries in family history research.

These resting places have become much more to me than merely a place to go and offer a bouquet of flowers. There are answers waiting to be discovered. The key to getting the answers is knowing which questions to ask.

In my experience, the best genealogists are not the ones with the best cameras, the best software, or the best gadgets–they are the ones with the best questions.

Curiosity is the most important tool to the successful genealogist. The next time you find yourself in a library of marble, take a few moments to let your curiosity run wild. Ask yourself:

- “Who are the people surrounding my family members?

- What are their stories?

- What do the etchings on their headstones mean?”

That curiosity will lead to the most remarkable discoveries and you will see for yourself how a piece of marble truly can break down a brick wall.

Below I’ve outlined the steps for finding family cemeteries and which questions you should be asking when you get there. Get inspired by my own examples of breaking down brick walls, and implement these methods I used for your own success!

Cemetery research step #1: Identify the cemetery

The first step in cemetery research is to identify the name of the cemetery where an ancestor was buried.

The best places to start looking are death certificates, funeral home records and obituaries. Each one of these records should contain the name of the cemetery where a family member was buried.

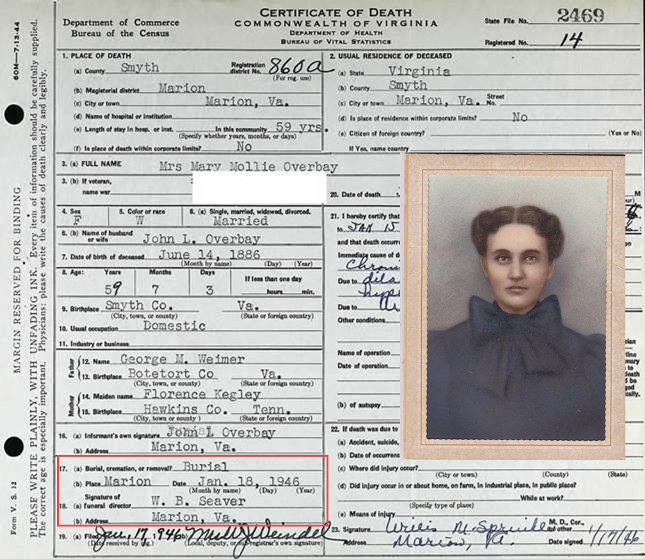

We sometimes fail to look beyond the names and dates on death certificates. If we get in the habit of taking the time to absorb all of the information on these important documents, we will find genealogical treasure.

Sometimes, the death certificate will not give us the name of the cemetery.

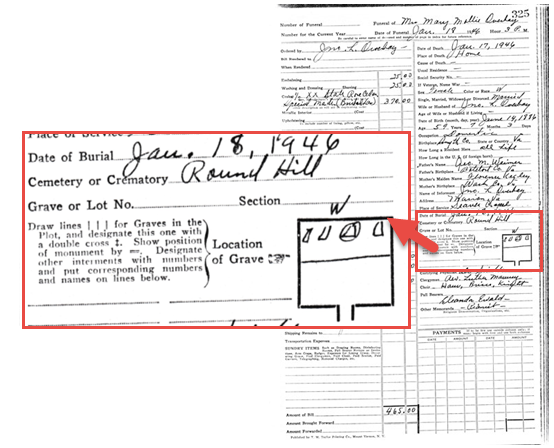

This was the case with my great-grandmother, Mollie Weimer Overbay. I was frustrated to see that the death certificate only indicated that she was buried, as opposed to cremated or removed to another location. While the certificate did not provide me with the name of a cemetery, it did offer the name of the funeral director: W.B. Seaver.

Luckily, I was able to follow this lead to the local funeral home. Within their records, I discovered that she was buried in Round Hill Cemetery, along with many of my other ancestors.

Cemetery research step #2: Locate the cemetery

Once you have located the name of the cemetery, several resources can guide you to its location.

Three helpful websites are listed below. Which you choose may depend on personal preference or familiarity but also on which site seems to have more records for the locales of most interest to you.

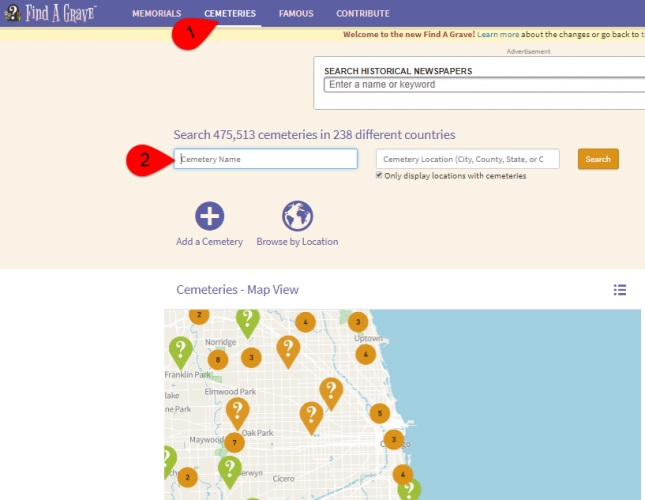

1. One of my favorite online resources is Find A Grave.

This website allows you to search for cemeteries all over the world.

At the home page, click on the Cemeteries tab (#1, below).

Then enter the name or location of the cemetery (#2). In the screenshot below, you can see part of the Google Maps interface that shows you the exact location of the cemetery, should you want to visit in person:

Find A Grave also has pictures of many of the headstones located within cemeteries.

2.  Billion Graves allows users to collect photos of headstones by using an iPhone/Android camera app.

Billion Graves allows users to collect photos of headstones by using an iPhone/Android camera app.

The app, available on Google Play and the App Store (for iPhone and iPad), tags the photos with the GPS location and, essentially, maps the cemetery as headstones are added.

Search for cemetery locations using the Billion Graves app or on the website by selecting the “Cemetery Search” option and then entering the name of the cemetery or a known address (to see it on Google Maps):

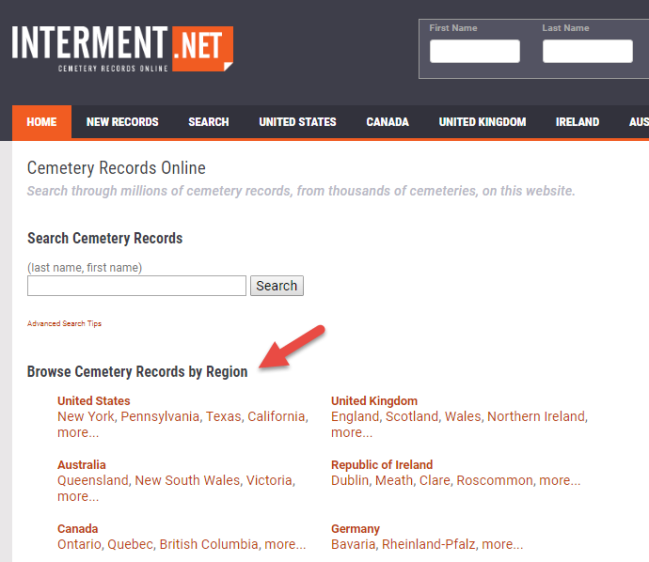

3. Interment.net can also be helpful.

From the home page, scroll down just a little until you see “Browse Cemetery Records by Region.” This can be especially helpful if you’re looking for all records within a specific county or other region. However, it’s not quite as useful if you’re trying to locate all cemeteries within a certain radius of a location, regardless of local boundaries.

In addition to these resources, it is essential to contact the local library, genealogical society, and/or historical society where your ancestors are buried. These organizations are well-known for maintaining detailed listings of local cemeteries within their collections.

For instance, within Smyth County (where I live) there is a four-volume set of books that contains the work of two local historians, Mack and Kenny Sturgill. They spent several years mapping local cemeteries and collecting the names on all of the headstones.

Although these books were completed in the 1990s, the information is still valuable to genealogists. Detailed driving directions were given to help future researchers locate cemeteries that would otherwise be difficult to locate. Many of them are on private property and even in the middle of cow pastures or wooded areas.

Furthermore, some of the headstones that were legible in the 1990s have now become difficult to decipher due to weathering or have altogether disappeared. It is likely that the counties in which you are conducting cemetery research offer similar resources.

Cemetery research step #3: Prepare for a visit

Once you have found the cemetery you want to visit, you will want to take the following items along with you to make the most of your visit:

- a camera

- pair of gloves

- grass clippers

- notebook and pen

- long pants

- sturdy shoes

You may also want to use a damp cloth to bring out the carvings on headstones. A side note: if you are like me and have an aversion to snakes, you will either choose to go on cemetery expeditions during the winter, or you will invest in a pair of snake chaps.

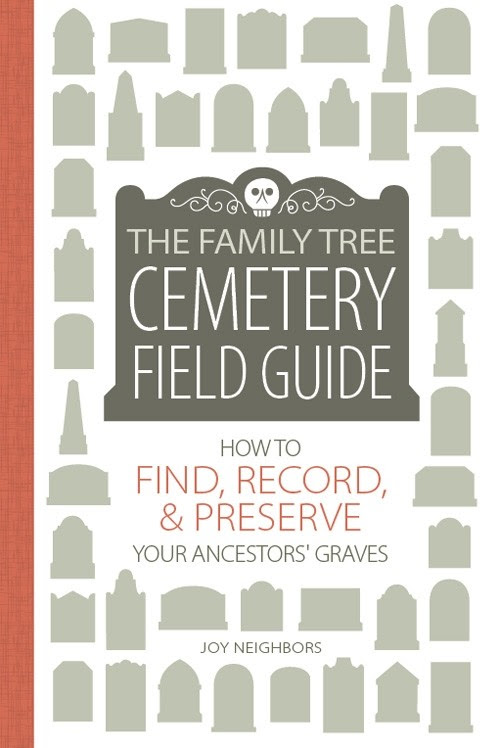

Get more help! The Family Tree Cemetery Field Guide (above) contains detailed step-by-steps for using FindAGrave and BillionsGraves, plus guides for understanding tombstone epitaphs and symbol meanings.

Disclosure: Genealogy Gems is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. Thank you for supporting our free podcast by using our link.

Cemetery research step #4: Visit and search for clues

This headstone shows something unusual: the couple’s ham radio call signs (the codes engraved just below their names).

The headstones found in cemeteries can reveal much about your family. You will find more than birth and death dates. If you look closely, you will discover symbols related to military service and religious beliefs, maiden names of the women in your family, and you may even find family members that you never knew about. Many times, you will find children buried in the family plot. Look around to see who is buried near your ancestors. It is likely that you will find connections to other family members when you are visiting the cemetery. These connections may lead you to break down long-standing brick walls within your family history.

In my own experience, there have been several instances in which cemetery research has helped shed light on a family mystery. I had grown up hearing that there were members of our family who had fought in the Civil War. Who were these men? What experiences did they have during the war? Where had they fought?

The answers to these questions came as the result of a visit to the cemetery. I had gone to Round Hill Cemetery to photograph the headstones of my Weimer ancestors. As I worked my way down the row, I encountered an unfamiliar name—William Henry Wymer. At the top of his headstone, there was a Southern Cross of Honor—a symbol used to denote a soldier who fought during the Civil War. Below his name was the following inscription: “Co. A, 6 VA RES, C.S.A:”

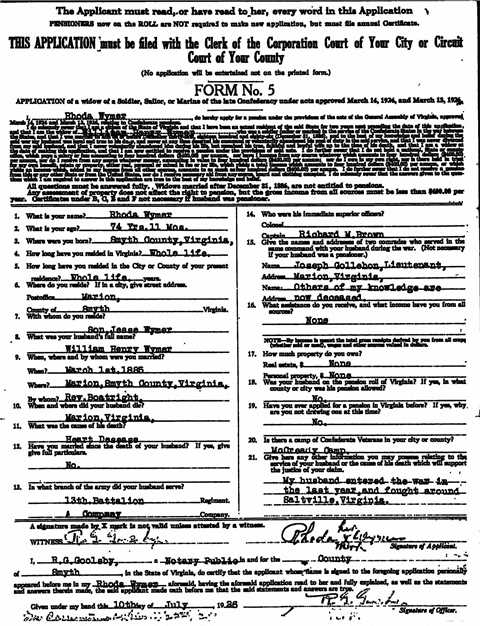

When I went home that afternoon, I began to search for more details. With some census research, I learned that he was the uncle of my great-grandmother, Mollie Weimer Overbay. Upon confirming his relationship to our family, I began searching for a pension application for his wife, Rhoda:

The application had been submitted in 1926 and told the story of William’s life. Among other things, I learned the answers to my questions about his service during the Civil War. His wife indicated that he enlisted during the last year of the war and was present during a well-known battle in our county—the Battle of Saltville. I am sure that my great-grandmother had grown up listening to tales of this battle and William’s experience during the war. The details of the story had been lost but were now re-discovered thanks to a trip to the cemetery.

Subtle clues like this one await you as you search out your own ancestors. The next time you make a trip to one of these libraries of marble, take a few moments to look closely at the clues that surround you. They may not be obvious, but they are there, waiting for your curiosity to uncover them. So, bring your cameras, your gloves, and your grass clippers to the cemetery on your next visit—but don’t forget to bring your questions and your ability to perceive the minute details, as you stand beneath the towering trees, among the rows of marble, waiting to offer up their long-held secrets.

More cemetery research tips

- Cemetery records: An alternative to death records

- How to find cemeteries in Google Earth

- How to read a faded tombstone without damaging the stone

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links and Genealogy Gems will be compensated if you make a purchase after clicking on these links (at no additional cost to you). Thank you for supporting Genealogy Gems.

Many years ago in Onaway , Michigan I encountered a lady that did further research for me on my grandmother’s family. She sent me a hand drawn picture of my 2 times great grandfather’s tombstone. For years I did not know what the lettering meant. One day I realized it was his civil war regiment and I was able to order his records.

Thank you for this article it is very pertinent.

This seems to be the help I need. I will keep this with my cemetery folder. An interesting point, my husband, 2 sons and I lived in Marion, Virginia from the fall of 1968 to the spring of 1970. We lived in Atkin’s Woodland on Hickory. I really liked the area, the mountains, the Redbuds and Dogwoods in bloom in the woods. Judy

Another important thing to take with you when doing cemetery research is insect repellent. Old cemeteries are prime habitat for mosquitoes, chiggers and ticks. I speak from experience.

Sometimes in researching cemeteries they have changed names. The one next to my house has had and gone by four names. One was the name of the town, then it was ran by a fraternal organization (I.O.O.F. also known as Odd Fellows) then it was deeded to our township and the name changed to the township. We have many cemeteries in our county that have had two to three names over time. So you may have to research from the time of death forward to the current day for the name now.

These are all such great comments! Dennis, what an amazing story about the drawing you were given. I’m so glad to hear that you were able to find out more about your great-great grandfather and his military service. This further illustrates just how important engravings are to research.

Judy, what a small world! I’m so glad the article helped you. If you ever find yourself back in Marion, send me a message. I would love to meet you and hear more about your time in Marion and your research.

Deborah, you are most certainly right about the insect repellant. It is easy to get eaten alive, without it. Virginia is especially bad for ticks. Thanks for that additional tip!

Sandra, I had not thought about name changes. That is a great point that could easily be overlooked and cause major frustration in the search for a cemetery. Thank you.

I love hearing your comments and stories….keep ‘em coming!

I would also recommend a flashlight, at least one umbrella (and not just for rain), a gardening kneeling pad, and even possibly one of those car windshield screens that are used to keep out the sun when a car is parked in the summer time.

The flashlight shown across the surface of a stone can create enough shadow to make the engraving easier to read (and doesn’t do any damage to the stone the way a rubbing can).

The umbrella(s) and/or windshield screen can help shade the stone for photographs – sunlight and your own shadow can make it hard to get a good shot.

And the gardening knee pad can allow you to kneel closer to the stone without getting your pants (and knees) wet or dirty.

Kathleen,

Those are great suggestions! I am going to try the windshield screen and flashlight tricks on my next trip to the cemetery. Thanks so much for sharing those tips.