“Results May Vary:” One Family’s DNA Ethnicity Percentages

Four members of a family–mom, dad, daughter, and son–tested with AncestryDNA. Their DNA ethnicity percentages vary. Why?

If you’ve taken a DNA test and received different ethnicity results than you expected and different from your family members, DNA expert Diahan Southard is here to explain why that happens.

There are limitations to the ethnicity results delivered by the various DNA testing companies.

For the most part, these admixture results are like that short film before the actual feature presentation. That feature presentation, in this case, is your genealogical match list. But, the short film is entertaining and certainly keeps your attention for a while. It can be especially interesting when you have several members of the same family tested so you can compare their ethnicity results.

Understanding Ethnicity Variance Within Immediate Families

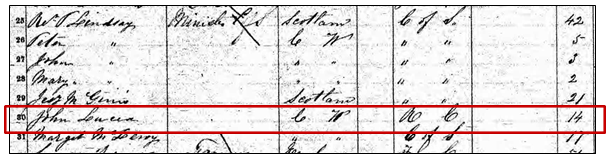

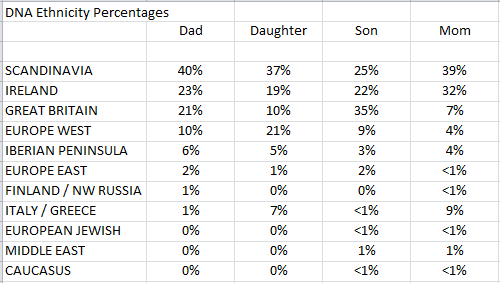

Let’s consider the real AncestryDNA test results of a family we’ll call the “Reese family:”

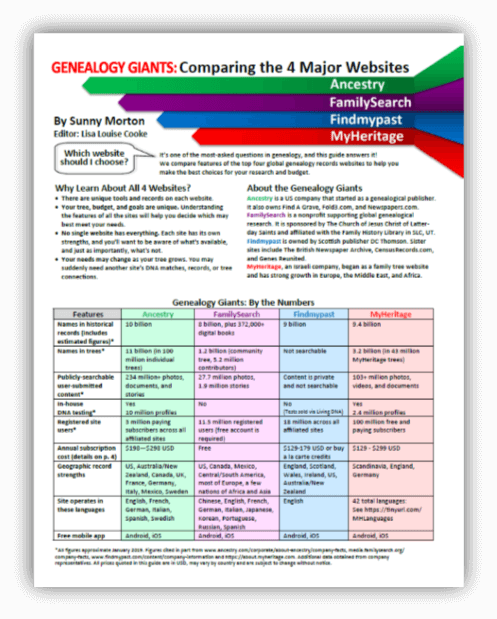

The Reese family has something to their great advantage: their family history indicates that they are mostly from Western Europe. This is a big advantage in the climate of today’s ethnicity results as all of the testing companies have far more data in their reference populations pouring out of western Europe than from anywhere else. (See this article for more information and the latest data on DNA reference populations on each testing company.) That means that in general, they are going to be better at telling you about your heritage from Ireland or England than they are at discovering that you are from China or India.

Looking at the ethnicity results for the Reese family, we are tempted to start applying our knowledge of DNA inheritance to the numbers we see. We know that each child should get half of their DNA from their mom and half from their dad. So our initial reaction might be to look at the dad’s 40% Scandinavian and mom’s 39% Scandinavian and assume that the child would also be about 40% (20% from dad and 20% from mom).

You can see that the daughter did, in fact, mostly measure up to that expectation with 37% Scandinavian. But the son, with only 25%, seems to have fallen short. The temptation to consider the daughter as the far better example of familial inheritance is strong (especially for us daughters, who are so often exceeding expectations!), but of course inaccurate. It is actually very difficult to look at the parent’s numbers alone and estimate the percentages that a child will receive.

A Snippet about SNPs (snips)

Remember that these numbers are tied to actual small pieces of DNA we call SNPs (snips).

Of the near 800,000 SNPs evaluated by your testing company, less than half of them are considered valuable for determining your ethnicity.

The majority of the SNPs tested are working to estimate how closely you are related to your genealogical cousin.

A good SNP for ethnicity purposes has to be ubiquitous enough to show up in many individuals from a given population, but unique enough to only show up in that population, and not any others.

It is a difficult balance to strike. But even when good SNPs are used, it is still difficult for the computer at your testing company to make accurate determinations about your ancestry.

New to using DNA for genealogy? Watch:

(Click on player to unmute sound)

Take the Great Britain line in the Reese family data, for example. The dad has 21% and the mom has 7%, so it would follow that the largest amount any child could have would be 28%. We see the daughter (of course!) falling well within that range at 10%, but the son is seven points above at 35%. How does THAT happen?!

Let’s go back to some basic biology.

Remember that you have two copies of each chromosome: one from mom and one from dad. These chromosomes are made up of strings of letters denoting the DNA code. That means that at each SNP location, you report two letters (again, one from mom and one from dad).

As the testing company is lining these letters up for comparison, they have to decide which letters go together: which are from the same chromosome and which set came from one single source.

Understanding Phasing

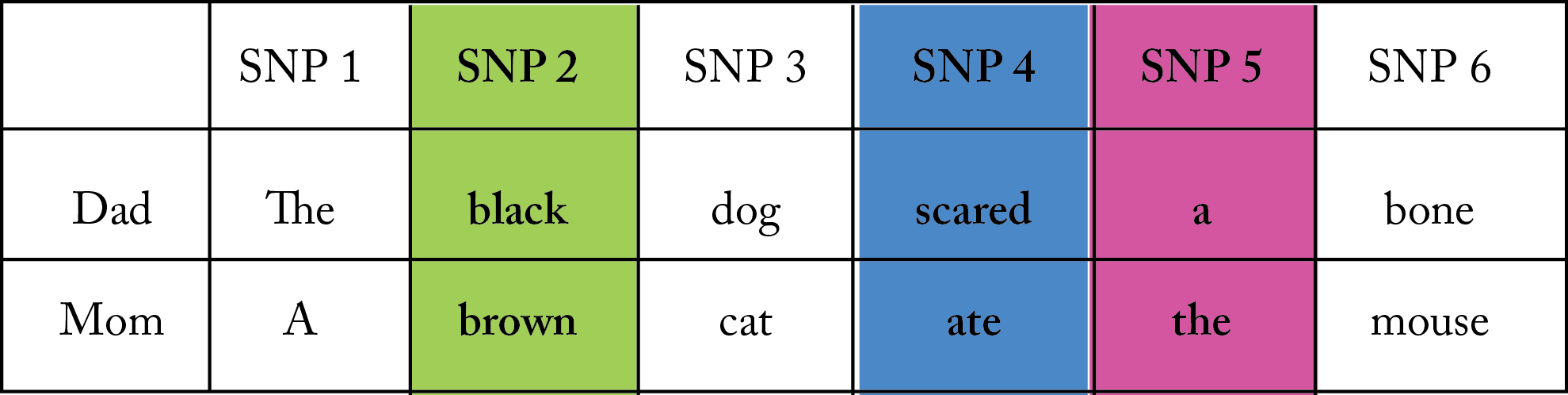

The process of determining which set of values goes on which line is called phasing. Often the inconsistencies you see in your DNA test results, whether it be in the matching or in the ethnicity, are because of problems the company has with this very difficult process.

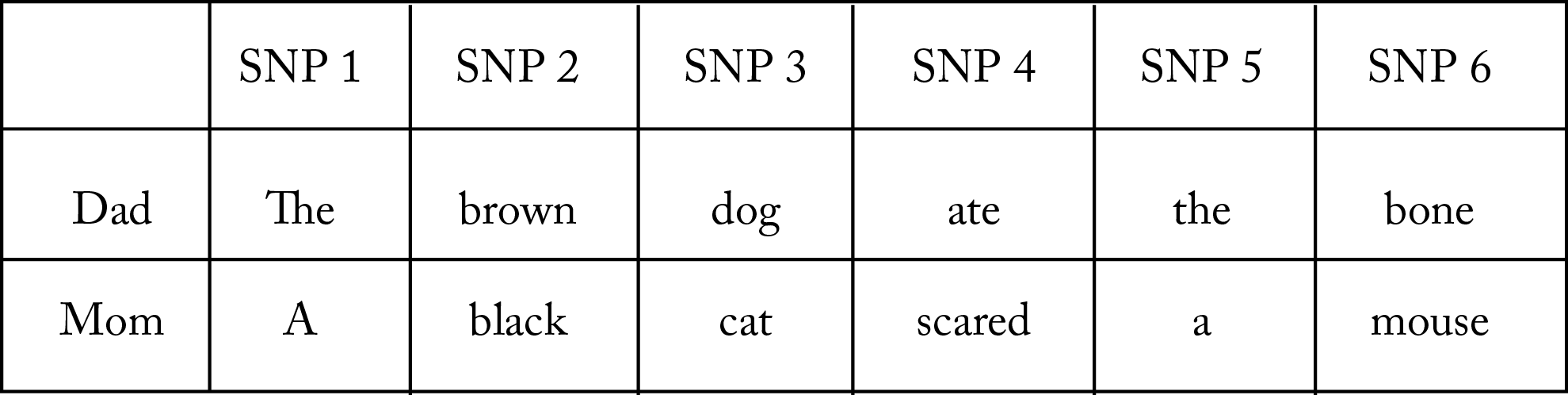

To illustrate how this works, let’s say we are trying to write two sentences: “The brown dog ate the bone.” and “A black cat scared a mouse.”

In this example, each word in each sentence represents a SNP. However, all the computer sees are two words, and it doesn’t know which word goes in which sentence. You can see in this example that it would be fairly easy to get it wrong. Mixing up a couple of words creates entirely new sentences with very different meanings, as shown in the examples below.

Phasing correct:

Phasing incorrect:

It’s important to understand that ethnicity results can, and will, vary among family members as well as different DNA testing companies for the reasons outlined above.

It can certainly be fun to compare what each family member received, but take it with a grain of salt. As you can see, a lot of genetic data is quickly lost over time.

In the Reese family example, we see that in one single generation this family has lost all traces of ancestry to several world regions. This really highlights the value of having the oldest generation of family members tested, to try to capture all that they have to offer in their DNA code.

Get more DNA help and plain-English explanations

If you’re feeling overwhelmed by DNA testing or struggling to make sense of the complex scientific data, our quick reference guides are exactly what you need!

Author and DNA expert Diahan Southard’s collection of DNA guides offer explanations in plain-English, helpful examples and graphics, and practical genealogical applications so you can make the most of your DNA results. Head over to the Genealogy Gems Store to browse our 10 DNA guides available in both print and digital download.

About the Author: Diahan Southard has worked with the Sorenson Molecular Genealogy Foundation, and has been in the genetic genealogy industry since it has been an industry. She holds a degree in Microbiology and her creative side helps her break the science up into delicious bite-sized pieces for you. She’s the author of a full series of DNA guides for genealogists.

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links and Genealogy Gems will be compensated if you make a purchase after clicking on these links (at no additional cost to you). Thank you for supporting Genealogy Gems!

This article was originally published on February 28, 2016 and updated on March 30, 2019.

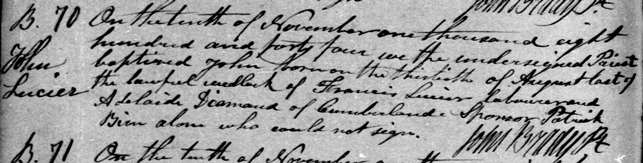

Recently we were contacted by a client who requested we begin researching her direct paternal ancestor. This ancestor was named John Lucy, of Ontario, Canada, and was of alleged Irish heritage.

Recently we were contacted by a client who requested we begin researching her direct paternal ancestor. This ancestor was named John Lucy, of Ontario, Canada, and was of alleged Irish heritage.