German Census Records DO Exist

For a long time, German census records were thought not to exist. But they do! A leading German genealogy expert tells us how they’ve been discovered and catalogued—and where you can learn about German census records that may mention your family.

Thanks to James M. Beidler for contributing this guest article. Read more below about him and the free classes he’ll be teaching in the Genealogy Gems booth at RootsTech 2018 in a few short weeks.

German census records DO exist

One of the truisms of researching ancestors in America is that the U.S. Census is a set of records that virtually every genealogist needs to use.

From its once-a-decade regularity to its easy accessibility, and the high percentage of survival to the present day, the U.S. Census helps researchers put together family groups across the centuries.

On the other hand, the thing that’s most distinctive about German census records is that for many years they were thought not to even exist.

For Exhibit A, look at this quote from a book published just a few years ago: “Most of the censuses that were taken have survived in purely statistical form, often with little information about individuals. There are relatively few censuses that are useful to genealogists.”

The book from which the above statement was taken is The Family Tree German Genealogy Guide. And the author of that book is … uh, well … me!

In my defense, this had been said by many specialists in German genealogy. The roots of this statement came from the honest assessment that Germany, which was a constellation of small states until the late 1700s and not a unified nation until 1871 when the Second German Empire was inaugurated, had few truly national records as a result of this history of disunity.

As with many situations in genealogy, we all can be victims of our own assumptions. The assumption here was that because it sounded right that Germany’s fractured, nonlinear history had produced so few other national records, those census records didn’t exist.

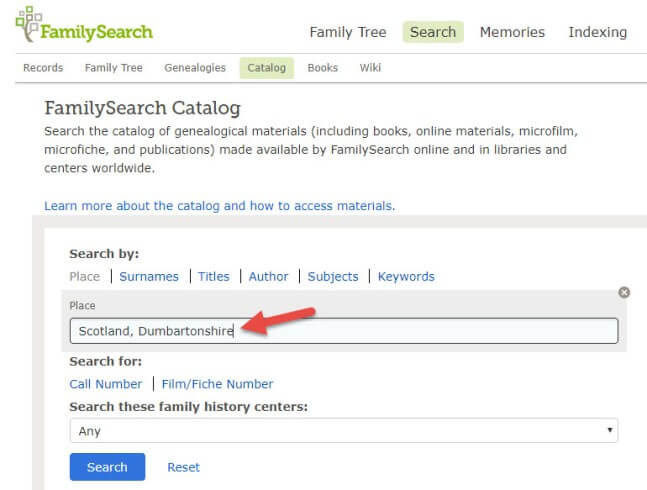

A few census records from northern German states (see below) had been microfilmed by the Family History Library, but for all intents and purposes, a greater understanding of the “lost” German census records had to wait for a project spearheaded by Roger P. Minert, the Brigham Young University professor who is one of the German genealogy world’s true scholars.

Finding lost and scattered German census records

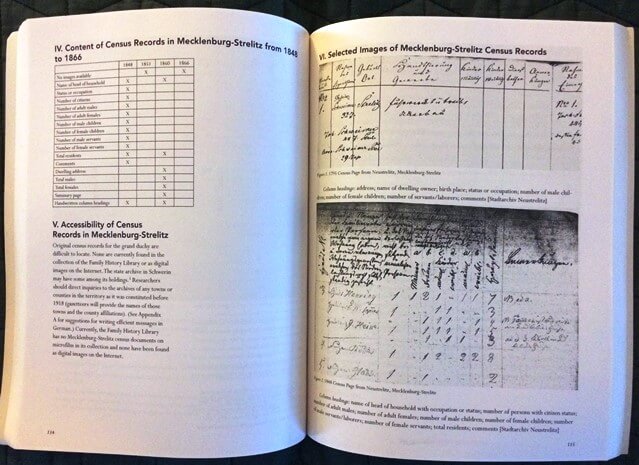

It can be said that Brigham Young University professor Roger Minert “wrote the book” on the German census. That’s because he literally did: German Census Records, 1816-1916: The When, Where, and How of a Valuable Genealogical Resource. A sample page is shown below.

Minert had a team help him get the project rolling by writing to archivists in Germany before he took a six-month sabbatical in Europe. During this time, he scoured repositories for samples of their German census holdings (To some extent, Minert’s project had echoes of an earlier work led by Raymond S. Wright III that produced Ancestors in German Archives: A Guide to Family History Sources).

What resulted from Minert’s project was the census book and a wealth of previously unknown information about German censuses.

While a few censuses date to the 18th century in the German states (some are called Burgerbücher, German for “citizen books”), Minert found that the initiation of customs unions during the German Confederation period beginning after Napoleon in 1815 was when many areas of Germany began censuses.

The customs unions (the German word is Zollverein) needed a fair way to distribute income and expenses among member states, and population was that way. But to distribute by population, a census was needed to keep count, and most every German state began to take a census by 1834.

Until 1867, the type of information collected from one German state to another varied considerably. Many named just the head of the household, while others provided everyone’s names. Some include information about religion, occupation and homeownership.

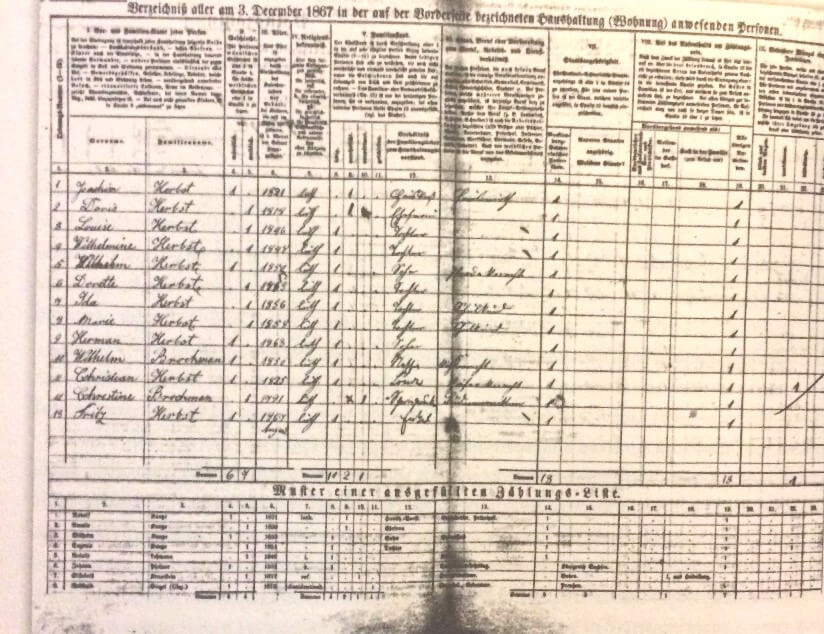

The year 1867 was a teeter-totter point Minert calls it “for all practical purposes the first national census.” Prussia—by then the dominant German state and whose king would become the emperor just a few years hence—spearheaded the census effort.

After the founding of the Second German Empire, a census was taken every five years (1875 – 1916, the last census being delayed by World War I). While there was some variance in data from one census to another, they all included the following data points:

- names of each individual,

- gender,

- birth (year and, later, specific dates),

- marital status,

- religion,

- occupation,

- citizenship,

- and permanent place of residence (if different from where they were found in the census).

While some of these censuses are found in regional archives within today’s German states, in many cases the census rolls were kept locally and only statistics were forwarded to more central locations.

Interestingly, there has been a lack of awareness even among German archivists that their repositories have these types of records! Minert says in his book that in three incidences, archivists told him their holdings included no census records, only to be proved wrong in short order.

Minert’s book goes through the old German Empire state by state and analyzes where researchers are likely to find censuses. For each state, there is also a chart on the pre-Empire censuses and what information they included.

Researchers wishing to access these records will often need to contact local archives. If you’ve uncovered a village of origin for an immigrant, you could contact them directly by searching for a website for the town, then emailing to ask (politely but firmly) whether the archives has census records.

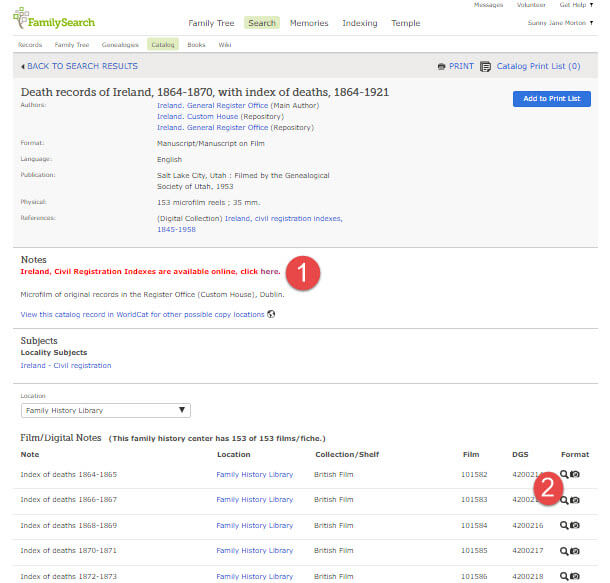

FamilySearch has placed online German census records for Mecklenburg-Schwerin (1867, 1890 and 1900; the one shown below is from 1867).

The Danish National Archives has some census records online for Schleswig-Holstein (much of the area was Danish until they lost a war with Prussia in 1864).

Other Census-Like Lists

In addition to these censuses, many areas of Germany have survivals of tax lists that serve as a record substitute with some data points that are similar to censuses. The lists generally show the name of the taxpayer and the amount of tax paid.

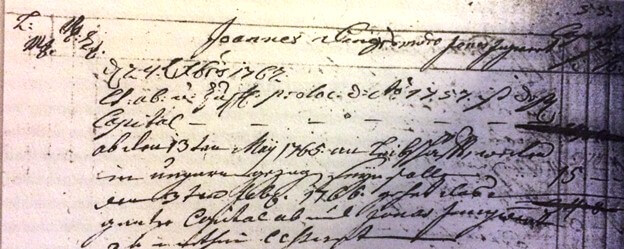

In some cases, versions of the lists that include the basis for the tax (usually the value of an interest in real or personal property) have survived. The lists may also include notes about emigration. Here’s a sample tax record from Steinwenden Pfalz.

Some of these tax lists are available in the Family History Library system.

The best “clearinghouse” that reports the holdings of various repositories in Germany is Wright’s Ancestors in German Archives. As with the census records, the best way to contact local archives directly would be to search for a website for the town. E-mail to ask whether such lists are kept in a local archive.

In my personal research, tax records have proved crucial. For example, they confirmed the emigration of my ancestor Johannes Dinius in the Palatine town of Steinwenden. These records showed the family had left the area a few months before Dinius’ 1765 arrival in America.

James M Beidler is the author of The Family Tree German Genealogy Guide and Trace Your German Roots Online.

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links and Genealogy Gems will be compensated if you make a purchase after clicking on these links (at no additional cost to you). Thank you for supporting Genealogy Gems